Spatio-Temporal

Misc

- Packages

- {cubble} (Vignette) - Organizing and wrangling space-time data. Addresses data collected at unique fixed locations with irregularity in the temporal dimension

- Handles sparse grids by nesting the time series features in a tibble or tsibble.

- {glmSTARMA} - (Double) Generalized Linear Models for Spatio-Temporal Data

- {magclass} - Data Class and Tools for Handling Spatial-Temporal Data

- Has datatable under the hood, so it should be pretty fast for larger data

- Conversions, basic calculations and basic data manipulation

- {mlr3spatiotempcv} - Extends the mlr3 machine learning framework with spatio-temporal resampling methods to account for the presence of spatiotemporal autocorrelation (STAC) in predictor variables

- {rasterVis} - Provides three methods to visualize spatiotemporal rasters:

hovmollerproduces Hovmöller diagramshorizonplotcreates horizon graphs, with many time series displayed in parallelxyplotdisplays conventional time series plots extracted from a multilayer raster.

- {SemiparMF} - Fits a semiparametric spatiotemporal (regression?) model for data with mixed frequencies, specifically where the response variable is observed at a lower frequency than some covariates.

- Combines a non-parametric smoothing spline for high-frequency data, parametric estimation for low-frequency and spatial neighborhood effects, and an autoregressive error structure

- {sdmTMB} - Implements spatial and spatiotemporal GLMMs (Generalized Linear Mixed Effect Models)

- {sftime} - A complement to {stars}; provides a generic data format which can also handle irregular (grid) spatiotemporal data

- {spStack} - Bayesian inference for point-referenced spatial data by assimilating posterior inference over a collection of candidate models using stacking of predictive densities.

- Currently, it supports point-referenced Gaussian, Poisson, binomial and binary outcomes.

- Highly parallelizable and hence, much faster than traditional Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithms while delivering competitive predictive performance

- Fits Bayesian spatially-temporally varying coefficients (STVC) generalized linear models without MCMC

- {stdbscan} - Spatio-Temporal DBSCAN Clustering

- {spTimer} (Vignette) - Spatio-Temporal Bayesian Modelling

- Models: Bayesian Gaussian Process (GP) Models, Bayesian Auto-Regressive (AR) Models, and Bayesian Gaussian Predictive Processes (GPP) based AR Models for spatio-temporal big-n problems

- Depends on {spacetime} and {sp}

- {stars} - Reading, manipulating, writing and plotting spatiotemporal arrays (raster and vector data cubes) in ‘R’, using ‘GDAL’ bindings provided by ‘sf’, and ‘NetCDF’ bindings by ‘ncmeta’ and ‘RNetCDF’

- Only handles full lattice/grid data

- It supercedes the {spacetime}, which extended the shared classes defined in {sp} for spatio-temporal data. {stars} uses PROJ and GDAL through {sf}.

- Easily convert spacetime objects to stars object with

st_as_stars(spacetime_obj)

- Easily convert spacetime objects to stars object with

- Has dplyr verb methods

- {cubble} (Vignette) - Organizing and wrangling space-time data. Addresses data collected at unique fixed locations with irregularity in the temporal dimension

- Resources

- SDS, Ch.13

- Geodata and Spatial Regression, Ch. 14

- Spatial Modelling for Data Scientists, Ch. 10

- Spatio-Temporal Statistics in R (See R >> Documents >> Geospatial)

- Spatial and Temporal Statistics

- It’s kind of a brief overview of spatial and temporal modeling separately. The spatio-temporal section at the end is also brief and pretty basic.

- There are things such as HMMs and GPs that I’m not yet familar with which could be interesting.

- Papers

- INLA-RF: A Hybrid Modeling Strategy for Spatio-Temporal Environmental Data

- Integrates a statistical spatio-temporal model with RF in an iterative two-stage framework.

- The first algorithm (INLA-RF1) incorporates RF predictions as an offset in the INLA-SPDE model, while the second (INLA-RF2) uses RF to directly correct selected latent field nodes. Both hybrid strategies enable uncertainty propagation between modeling stages, an aspect often overlooked in existing hybrid approaches.

- A Kullback-Leibler divergence-based stopping criterion.

- Effective Bayesian Modeling of Large Spatiotemporal Count Data Using Autoregressive Gamma Processes

- Introduces spatempBayesCounts package but evidently it hasn’t been publicly released yet

- Amortized Bayesian Inference for Spatio-Temporal Extremes: A Copula Factor Model with Autoregression

- INLA-RF: A Hybrid Modeling Strategy for Spatio-Temporal Environmental Data

- Notes from

- spacetime: Spatio-Temporal Data in R - It’s been superceded by {stars}, but there didn’t seem to be much about working with vector data in {stars} vignettes. So, it seemed like a better place to start for a beginner, and I think the concepts might transfer since the packages were created by the same people. Some packages still use sp and spacetime, so it could be useful in using with those packages

- Spatio-Temporal Interpolation using gstat

- Recommended Workflow (source)

- Go from simple analysis to complex (analysis) to get a feel for your data first. A lot of times, you probably will not need to do a spatio-temporal analysis at all.

- Steps

- Run univariate/multivariate analysis while ignoring space and time variables

- Aggregate over locations (e.g. average across all time points for each location). Then run spatial analysis (e.g. spatial regression, kriging, etc.).

- Looking for patterns, hotspots, etc.

group_by(location) |> summarize(median_val = median(val))- e.g. min, mean, median, or max depending on the project

- Aggregate over time (e.g. average across all locations for each time point). Then run time series analysis (e.g. moving average, arima, etc.).

- Looking trend, seasonality, shocks, etc.

group_by(date) |> summarize(max_val = max(val))

- Select interesting or important locations (e.g. top sales store, crime hotspot) and run a time series analysis on that location’s data

- Select interesting or important time points (e.g. holiday, noon) and run a spatial analysis on that time point

- Run a spatio-temporal analysis

Terms

- Anisotropy

Spatial Anisotropy means that spatial correlation depends not only on distance between locations but also direction.

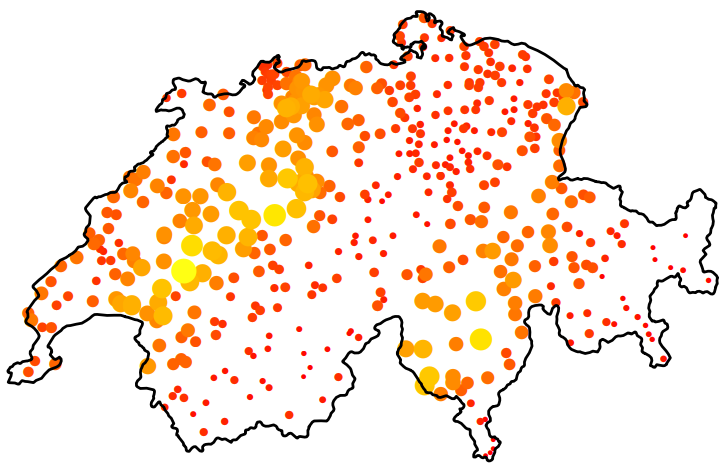

- The size and color of circle represent rainfall values

- The figure (source) demonstrates spatial anisotropy with alternating stripes of large and small circles from left to right, southwest to northeast.

- Standard Kriging assumes isotropy (uniform in all directions) and uses an omnidirectional variogram that averages spatial correlation across all directions. Violation of isotropy can bias predictions; overestimate uncertainty in “stronger” directions (and vice versa); and the predictions will fail to capture patterns.

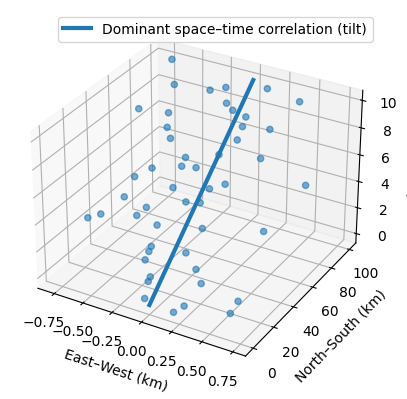

Spatio-Temporal Anisotropy refers to directional dependence in correlation that varies across both space and time dimensions

- Example: If you are mapping a pollution plume moving North at 10 km/h, the correlation structure is not just “longer in the North-South direction.”

- It is tilted in the space-time cube where time is the vertical in the 3d representation.

- A vertical correlation (no anisotropy) would start at the bottom of the line and be parallel to the z-axis (time)

- If you are measuring something that doesn’t move—like soil quality at a specific GPS coordinate—the time correlation is vertical

- With a pollution plume, the time correlation will “tilt” because pollution values will be more similar in different locations as time increases.

- It is tilted in the space-time cube where time is the vertical in the 3d representation.

- Example: If you are mapping a pollution plume moving North at 10 km/h, the correlation structure is not just “longer in the North-South direction.”

- Non-Spatial Microscale Effects - Sources of variability that do not necessarily decay with spatial distance over your sampling resolution, but appear as excess semivariance at short lags (i.e. possible explanations for a nugget effect)

- Measurement Error

- Instrument noise

- Calibration differences across monitors

- Local siting effects (height, enclosure, nearby obstructions

- Sub-Grid Physical Variability

- Street-level pollution vs background air

- Near-road vs off-road effects

- Local point sources (traffic lights, factories, heating units)

- Omitted Covariates

- Elevation

- Land use

- Urban/rural classification

- Meteorology (boundary layer height, wind exposure)

- Regime Mixing in Time

- Seasonal transitions

- Weather regimes

- Policy or emissions changes

- Measurement Error

- UNIX Time - The number of seconds between a particular time and the UNIX epoch, which is January the 1st 1970 GMT.

Should have 10 digits. If it has 13, then milliseconds are also included.

Convert to POSIXlt

data$TIME <- as.POSIXlt(as.numeric(substr( paste(data$generation_time), start = 1, stope = 10)), origin = "1970-01-01")substris subsetting the 1st 10 digitspasteis converting the numeric to a string. I’d tryas.charater.

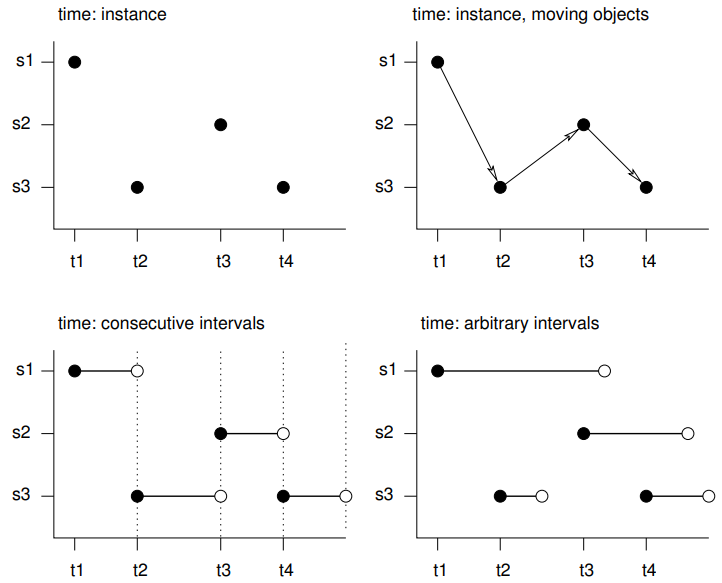

Grid Layouts

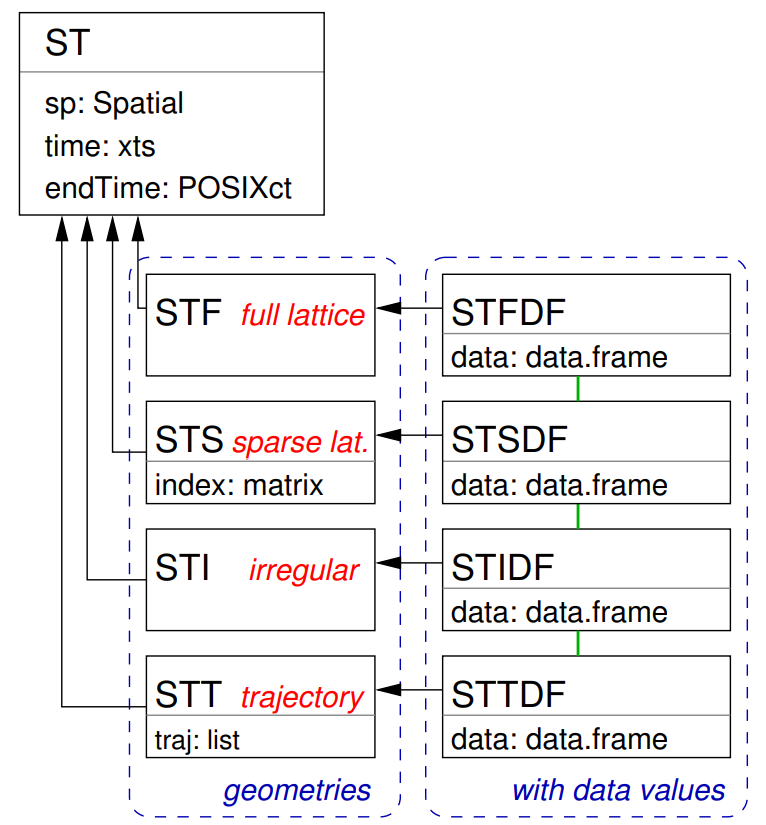

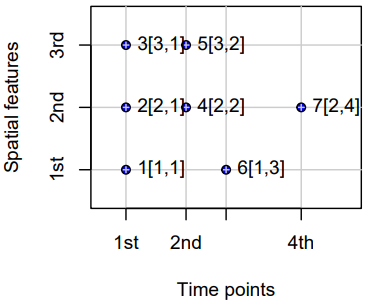

- {spacetime} Classes

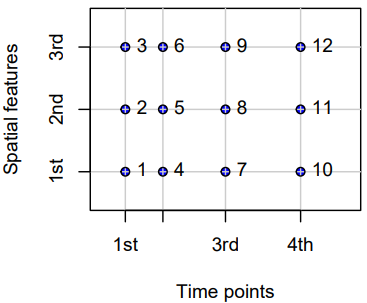

- Full-Grids

- Each coordinate (spatial feature vs. time) for each time point has a value (which can be NA) — i.e. a fixed set of spatial entities and a fixed set of time points.

- Examples

- Regular (e.g., hourly) measurements of air quality at a spatially irregular set of points (measurement stations)

- Yearly disease counts for a set of administrative regions

- A sequence of rainfall images (e.g., monthly sums), interpolated to a spatially regular grid. In this example, the spatial feature (images) are grids themselves.

- Sparse Grids

- Only coordinates (spatial feature vs. time) that have a value are included (no NA values)

- Use Cases

- Space-time lattices where there are many missing or trivial values

- e.g. grids where points represent observed fires, and points where no fires are recorded are discarded.

- Each spatial feature has a different set of time points

- e.g. where spatial feaatures are regions and a point indicates when and where a crime takes place. Some regions may have frequent crimes while others hardly any.

- When spatial features vary with time

- Scenarios

- Some locations only exist during certain periods.

- Measurement stations move or appear/disappear.

- Remote sensing scenes shift or have different extents.

- Administrative boundaries change (e.g., counties/tracts splitting or merging).

- Example: Suppose you have monthly satellite images of vegetation over a region for three months

- January: the satellite covers tiles A, B, and C

- February: cloud cover obscures tile B; only A and C are available

- March: a different orbital path covers B and D (a new area)

- Example: Crime locations over time for a city

- In 2018, you have GPS points for all recorded crimes that year (randomly scattered).

- In 2019, you have a completely different set of GPS points (different crimes, different places).

- The number of points per year also varies.

- Scenarios

- Space-time lattices where there are many missing or trivial values

- Irregular Grids

- Time and space points of measured values have no apparent organization: for each measured value the spatial feature and time point is stored, as in the long format.

- No underlying lattice structure or indexes. Each observation is a standalone (space, time) pair. Repeated values are possible.

- Essentially just a dataframe with a geometry column, datetime column, and value column.

- Use Cases

- Mobile sensors or moving animals: each record has its own location and timestamp — no fixed grid or station network.

- Lightning strikes: purely random events in continuous space-time.

- Trajectory Grids

- Trajectories cover the case where sets of (irregular) space-time points form sequences, and depict a trajectory.

- Their grouping may be simple (e.g., the trajectories of two persons on different days), nested (for several objects, a set of trajectories representing different trips) or more complex (e.g., with objects that split, merge, or disappear).

- Examples

- Human trajectories

- Mobile sensor measurements (where the sequence is kept, e.g., to derive the speed and direction of the sensor)

- Trajectories of tornados where the tornado extent of each time stamp can be reflected by a different polygon

Data Formats

- Misc

- {spacetime} supported Time Classes: Date, POSIXt, timeDate ({timeDate}), yearmon ({zoo}), and yearqtr ({zoo})

- Data and Spatial Classes:

- Points: Data having points support should use the SpatialPoints class for the spatial feature

- Polygons: Values reflect aggregates (e.g., sums, or averages) over the polygon (SpatialPolygonsDataFrame, SpatialPolygons)

- Grids: Values can be point data or aggregates over the cell.

stConstructcreates “a STFDF (full lattice/full grid) object if all space and time combinations occur only once, or else an object of class STIDF (irregular grid), which might be coerced into other representations.”- Latitude and Longitude to using {sp}

Example: (source)

# Create a SpatialPointsDataFrame coordinates(df) <- ~ LON + LAT projection(df) <- CRS("+init=epsg:4326") # Transform into Mercator Projection # SpatialPointsDataFrame with coordinates in meters. ozone.UTM <- spTransform(df, CRS("+init=epsg:3395")) # SpatialPoints ozoneSP <- SpatialPoints(ozone.UTM@coords, CRS("+init=epsg:3395"))

- Long - The full spatio-temporal information (i.e. response value) is held in a single column, and location and time are also single columns.

Example: Private capital stock (?)

#> state year region pcap hwy water util pc gsp #> 1 ALABAMA 1970 6 15032.67 7325.80 1655.68 6051.20 35793.80 28418 #> 2 ALABAMA 1971 6 15501.94 7525.94 1721.02 6254.98 37299.91 29375 #> 3 ALABAMA 1972 6 15972.41 7765.42 1764.75 6442.23 38670.30 31303 #> 4 ALABAMA 1973 6 16406.26 7907.66 1742.41 6756.19 40084.01 33430 #> 5 ALABAMA 1974 6 16762.67 8025.52 1734.85 7002.29 42057.31 33749- Each row is a single time unit and space unit combination.

- This is likely not the row order you want though. I think these spatio-temporal object creation functions want ordered by time, then by space. (See Example)

Example: Create full grid spacetime object from a long table (7.2 Panel Data in {spacetime} vignette)

head(df_data); tail(df_data) #> state year region pcap hwy water util pc gsp emp unemp #> 1 ALABAMA 1970 6 15032.67 7325.80 1655.68 6051.20 35793.80 28418 1010.5 4.7 #> 18 ARIZONA 1970 8 10148.42 4556.81 1627.87 3963.75 23585.99 19288 547.4 4.4 #> 35 ARKANSAS 1970 7 7613.26 3647.73 644.99 3320.54 19749.63 15392 536.2 5.0 #> 52 CALIFORNIA 1970 9 128545.36 42961.31 17837.26 67746.79 172791.92 263933 6946.2 7.2 #> 69 COLORADO 1970 8 11402.52 4403.21 2165.03 4834.28 23709.75 25689 750.2 4.4 #> 86 CONNECTICUT 1970 1 15865.66 7237.14 2208.10 6420.42 24082.38 38880 1197.5 5.6 #> state year region pcap hwy water util pc gsp emp unemp #> 731 VERMONT 1986 1 2936.44 1830.16 335.51 770.78 6939.39 7585 234.4 4.7 #> 748 VIRGINIA 1986 5 28000.68 14253.92 4786.93 8959.83 71355.78 88171 2557.7 5.0 #> 765 WASHINGTON 1986 9 41136.36 11738.08 5042.96 24355.32 66033.81 67158 1769.9 8.2 #> 782 WEST_VIRGINIA 1986 5 10984.38 7544.99 834.01 2605.38 35781.74 21705 597.5 12.0 #> 799 WISCONSIN 1986 3 26400.60 10848.68 5292.62 10259.30 60241.65 70171 2023.9 7.0 #> 816 WYOMING 1986 8 5700.41 3400.96 565.58 1733.88 27110.51 10870 196.3 9.0 yrs <- 1970:1986 vec_time <- as.POSIXct(paste(yrs, "-01-01", sep=""), tz = "GMT") head(vec_time) #> [1] "1970-01-01 GMT" "1971-01-01 GMT" "1972-01-01 GMT" "1973-01-01 GMT" "1974-01-01 GMT" "1975-01-01 GMT" head(spatial_geom_ids) #> [1] "alabama" "arizona" "arkansas" "california" "colorado" "connecticut" class(geom_states) #> [1] "SpatialPolygons" #> attr(,"package") #> [1] "sp"- The names of the objects above don’t the match the ones in the example, but I wanted names that were more informative about what types of objects were needed. The package documentation and vignette are spotty with their descriptions and explanations.

- The row order of the spatial geometry object should match the row order of the spatial feature column (in each time section) of the dataframe.

- The data_df only has the state name (all caps) and the year as space and time features.

- spatial_geom_ids shows the order of the spatial geometry object (state polygons) which are state names in alphabetical order.

- At least in this example, the geometry object (geom_states) didn’t store the actual state names. It just used a id index (e.g. ID1, ID2, etc.)

st_data <- STFDF(sp = geom_states, time = vec_time, data = df_data) length(st_data) #> [1] 816 nrow(df_data) #> [1] 816 class(st_data) #> [1] "STFDF" #> attr(,"package") #> [1] "spacetime" df_st_data <- as.data.frame(st_data) head(df_st_data[1:6]); tail(df_st_data[1:6]) #> V1 V2 sp.ID time endTime timeIndex #> 1 -86.83042 32.80316 ID1 1970-01-01 1971-01-01 1 #> 2 -111.66786 34.30060 ID2 1970-01-01 1971-01-01 1 #> 3 -92.44013 34.90418 ID3 1970-01-01 1971-01-01 1 #> 4 -119.60154 37.26901 ID4 1970-01-01 1971-01-01 1 #> 5 -105.55251 38.99797 ID5 1970-01-01 1971-01-01 1 #> 6 -72.72598 41.62566 ID6 1970-01-01 1971-01-01 1 #> V1 V2 sp.ID time endTime timeIndex #> 811 -72.66686 44.07759 ID44 1986-01-01 1987-01-01 17 #> 812 -78.89655 37.51580 ID45 1986-01-01 1987-01-01 17 #> 813 -120.39569 47.37073 ID46 1986-01-01 1987-01-01 17 #> 814 -80.62365 38.64619 ID47 1986-01-01 1987-01-01 17 #> 815 -90.01171 44.63285 ID48 1986-01-01 1987-01-01 17 #> 816 -107.55736 43.00390 ID49 1986-01-01 1987-01-01 17- So combining of these objects into a spacetime object doesn’t seemed be based any names (e.g. a joining variable) of the elements of these separate objects.

- STFDF arguments:

- sp: An object of class Spatial, having n elements

- time: An object holding time information, of length m;

- data: A data frame with n*m rows corresponding to the observations

- Converting back to a dataframe adds 6 new columns to df_data:

- V1, V2: Latitude, Longitude

- sp.ID: IDs within the spatial geomtry object (geom_states)

- time: Time object values

- endTime: Used for intervals

- timeIndex: An index of time “sections” in the data dataframe. (e.g. 1:17 for 17 unique year values)

- Space-wide - Each space unit is a column

Example: Wind speeds

#> year month day RPT VAL ROS KIL SHA BIR DUB CLA MUL #> 1 61 1 1 15.04 14.96 13.17 9.29 13.96 9.87 13.67 10.25 10.83 #> 2 61 1 2 14.71 16.88 10.83 6.50 12.62 7.67 11.50 10.04 9.79 #> 3 61 1 3 18.50 16.88 12.33 10.13 11.17 6.17 11.25 8.04 8.50 #> 4 61 1 4 10.58 6.63 11.75 4.58 4.54 2.88 8.63 1.79 5.83 #> 5 61 1 5 13.33 13.25 11.42 6.17 10.71 8.21 11.92 6.54 10.92 #> 6 61 1 6 13.21 8.12 9.96 6.67 5.37 4.50 10.67 4.42 7.17- Each row is a unique time unit

Example: Create full grid spacetime object from a space-wide table (7.3 Interpolating Irish Wind in {spacetime} vignette)

class(mat_wind_velos) #> [1] "matrix" "array" dim(mat_wind_velos) #> [1] 6574 12 mat_wind_velos[1:6, 1:6] #> RPT VAL ROS KIL SHA BIR #> [1,] 0.47349183 0.4660816 0.29476767 -0.12216857 0.37172544 -0.0549353 #> [2,] 0.43828072 0.6342761 0.04762928 -0.48431251 0.23530275 -0.3264873 #> [3,] 0.76797566 0.6297610 0.20133157 -0.03446898 0.07989186 -0.5358676 #> [4,] 0.01118683 -0.4751407 0.13684623 -0.78709720 -0.79381717 -1.1049744 #> [5,] 0.29298091 0.2851083 0.09805298 -0.54439303 0.02147079 -0.2707680 #> [6,] 0.27715281 -0.2860777 -0.06624749 -0.47759668 -0.66795421 -0.8085874 class(wind$time) #> [1] "POSIXct" "POSIXt" wind$time[1:5] #> [1] "1961-01-01 12:00:00 GMT" "1961-01-02 12:00:00 GMT" "1961-01-03 12:00:00 GMT" "1961-01-04 12:00:00 GMT" "1961-01-05 12:00:00 GMT" class(geom_stations) #> [1] "SpatialPoints" #> attr(,"package") #> [1] "sp"- See Long >> Example >> Create full grid spacetime object for a more detailed breakdown of creating these objects

- The order of station geometries in geom_stations should match the order of the columns in mat_wind_velos

- In the vignette, the data used to create the geometry object is ordered according to the matrix using

match. See R, Base R >> Functions >>matchfor the code.

- In the vignette, the data used to create the geometry object is ordered according to the matrix using

st_wind = stConstruct( # space-wide matrix x = mat_wind_velos, # index for spatial feature/spatial geometries space = list(values = 1:ncol(mat_wind_velos)), # datetime column from original data time = wind$time, # spatial geometry SpatialObj = geom_stations, interval = TRUE ) class(st_wind) #> [1] "STFDF" #> attr(,"package") #> [1] "spacetime" df_st_wind <- as.data.frame(st_wind) dim(df_st_wind) #> [1] 78888 7 head(df_st_wind); tail(df_st_wind) #> coords.x1 coords.x2 sp.ID time endTime timeIndex values #> 1 551716.7 5739060 1 1961-01-01 12:00:00 1961-01-02 12:00:00 1 0.4734918 #> 2 414061.0 5754361 2 1961-01-01 12:00:00 1961-01-02 12:00:00 1 0.4660816 #> 3 680286.0 5795743 3 1961-01-01 12:00:00 1961-01-02 12:00:00 1 0.2947677 #> 4 617213.8 5836601 4 1961-01-01 12:00:00 1961-01-02 12:00:00 1 -0.1221686 #> 5 505631.2 5838902 5 1961-01-01 12:00:00 1961-01-02 12:00:00 1 0.3717254 #> 6 574794.2 5882123 6 1961-01-01 12:00:00 1961-01-02 12:00:00 1 -0.0549353 #> coords.x1 coords.x2 sp.ID time endTime timeIndex values #> 78883 682680.1 5923999 7 1978-12-31 12:00:00 1979-01-01 12:00:00 6574 0.8600970 #> 78884 501099.9 5951999 8 1978-12-31 12:00:00 1979-01-01 12:00:00 6574 0.1589576 #> 78885 608253.8 5932843 9 1978-12-31 12:00:00 1979-01-01 12:00:00 6574 0.1536922 #> 78886 615289.0 6005361 10 1978-12-31 12:00:00 1979-01-01 12:00:00 6574 0.1325158 #> 78887 434818.6 6009945 11 1978-12-31 12:00:00 1979-01-01 12:00:00 6574 0.2058466 #> 78888 605634.5 6136859 12 1978-12-31 12:00:00 1979-01-01 12:00:00 6574 1.0835638- space has a confusing description. Here it’s just a numerical index for the number of columns of mat_wind_velos which would match an index/order for the geometries in geom_stations.

- interval = TRUE, since the values are daily mean wind speed (aggregation)

- See Time and Movement section

- df_st_wind is in long format

- Time-wide - Each time unit is a column

Example: Counts of SIDS

#> NAME BIR74 SID74 NWBIR74 BIR79 SID79 NWBIR79 #> 1 Ashe 1091 1 10 1364 0 19 #> 2 Alleghany 487 0 10 542 3 12 #> 3 Surry 3188 5 208 3616 6 260 #> 4 Currituck 508 1 123 830 2 145 #> 5 Northampton 1421 9 1066 1606 3 1197- SID74 contains to the infant death syndrome cases for each county at a particular time period (1974-1984). SID79 are SIDS deaths from 1979-84.

- NWB is non-white births, BIR is births.

- Each row is a spatial unit and unique

- SID74 contains to the infant death syndrome cases for each county at a particular time period (1974-1984). SID79 are SIDS deaths from 1979-84.

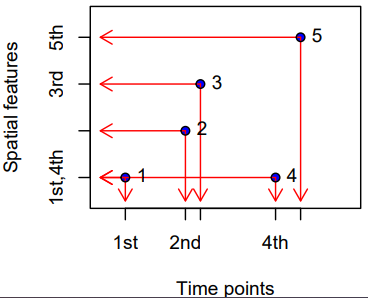

- Time and Movement

- s1 refers to the first feature/location, t1 to the first time instance or interval, thick lines indicate time intervals, arrows indicate movement. Filled circles denote start time, empty circles end times, intervals are right-closed

- Spatio-temporal objects essentially needs specification of the spatial, the temporal, and the data values

- Intervals - The spatial feature (e.g. location) or its associated data values does not change during this interval, but reflects the value or state during this interval (e.g. an average)

- e.g. yearly mean temperature at a set of locations

- Instants - Reflects moments of change (e.g., the start of the meteorological summer), or events with a zero or negligible duration (e.g., an earthquake, a lightning).

- Movement - Reflects objects may change location during a time interval. For time instants. locations are at a particular moment, and movement occurs between registered (time, feature) pairs and must be continuous.

- Trajectories - Where sets of (irregular) space-time points form sequences, and depict a trajectory.

- Their grouping may be simple (e.g., the trajectories of two persons on different days), nested (for several objects, a set of trajectories representing different trips) or more complex (e.g., with objects that split, merge, or disappear).

- Examples

- Human trajectories

- Mobile sensor measurements (where the sequence is kept, e.g., to derive the speed and direction of the sensor)

- Trajectories of tornados where the tornado extent of each time stamp can be reflected by a different polygon

EDA

Misc

- Also see EDA, Time Series

- Check for duplicate locations:

Kriging cannot handle duplicate locations and returns an error, generally in the form of a “singular matrix”.

Examples:

dupl <- sp::zerodist(spatialpoints_obj) # sf dup <- duplicated(st_coordinates(sf_obj)) log_mat <- st_equals(sf_obj) # terra (or w/spatraster, spatvector) d <- distance(lon_lat_mat) log_mat <- which(d == 0, arr.ind = TRUE) # base r dup_indices <- duplicated(df[, c("lat", "long")]) # within a tolerance # Find points within 0.01 distance dup_pairs <- st_is_within_distance(sf_obj, dist = 0.01, sparse = FALSE)

General

-

Code

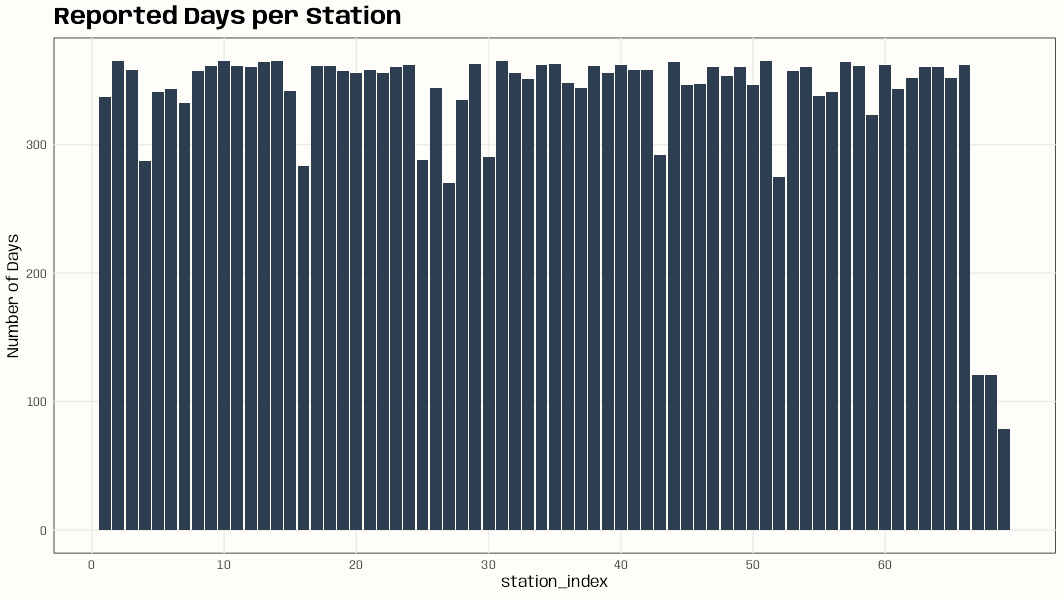

library(dplyr); library(ggplot2) data(DE_RB_2005, package = "gstat") class(DE_RB_2005) #> [1] "STSDF" tibble(station_index = DE_RB_2005@index[,1]) |> count(station_index) |> ggplot(aes(x = station_index, y = n)) + geom_col(fill = "#2c3e50") + scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq.int(0, length(unique(DE_RB_2005@index[,1])), 10)) + ylab("Number of Days") + ggtitle("Reported Days per Station") + theme_notebook() # station names for some indexes w/low number of days row.names(DE_RB_2005@sp)[c(4, 16, 52, 67, 68, 69)] #> [1] "DEUB038" "DEUB039" "DEUB026" "DEHE052.1" "DEHE042.1" "DEHE060"- If there’s there are locations with few observations on too many days, this can result in volatile variograms.

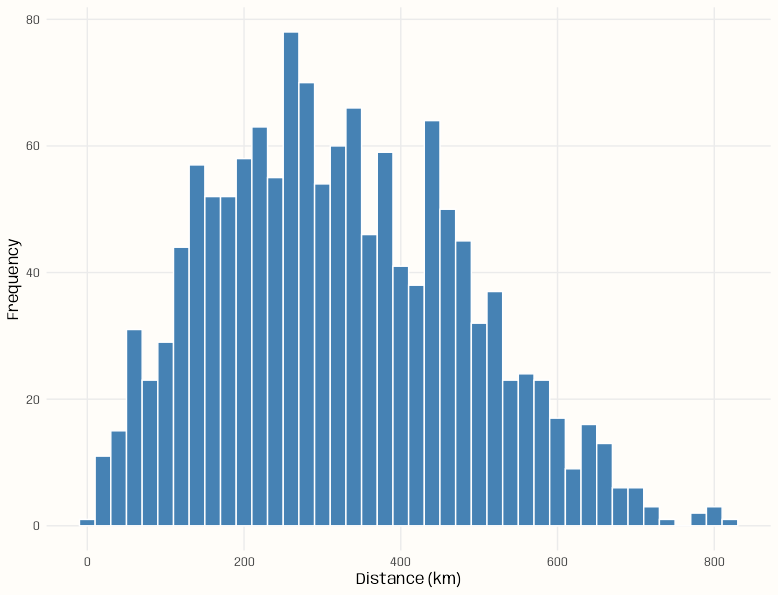

Example: Counts of pairwise distances between locations

Code

pacman::p_load( spacetime, sf, ggplot2 ) data(air) # get rural location time series from 2005 to 2010 rural <- STFDF( sp = stations, time = dates, data = data.frame(PM10 = as.vector(air)) ) rr <- rural[,"2005::2010"] # remove station ts w/all NAs unsel <- which(apply( as(rr, "xts"), 2, function(x) all(is.na(x))) ) r5to10 <- rr[-unsel,] sf_locs <- st_as_sf(r5to10@sp) # Calculate pairwise distances mat_dist_sf <- st_distance(sf_locs) # Convert to kilometers mat_dist_sf_km <- units::set_units(mat_dist_sf, km) |> units::drop_units() dim(mat_dist_sf_km) #> [1] 53 53 tibble::tibble( distance = mat_dist_sf_km[upper.tri(mat_dist_sf_km)] ) |> ggplot(aes(x = distance)) + geom_histogram( binwidth = 20, fill = "steelblue", color = "#FFFDF9FF") + labs(x = "Distance (km)", y = "Frequency") + theme_notebook() summary(mat_dist_sf_km[upper.tri(mat_dist_sf_km)]) #> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. #> 7.027 197.849 308.533 321.976 439.895 813.742- The bin width is set to 20 km (which is the setting for the variogram model in the {gstat} vignette)

- For kriging, ideally we’d want at least around 100 pairwise distances in each of the first few bins (short pairwise distances) for a stable range estimate, but no pairwise distance bin has that many. (See Geospatial, Kriging >> Bin Width)

- This is due to there only being 53 locations and the selection of only rural locations

-

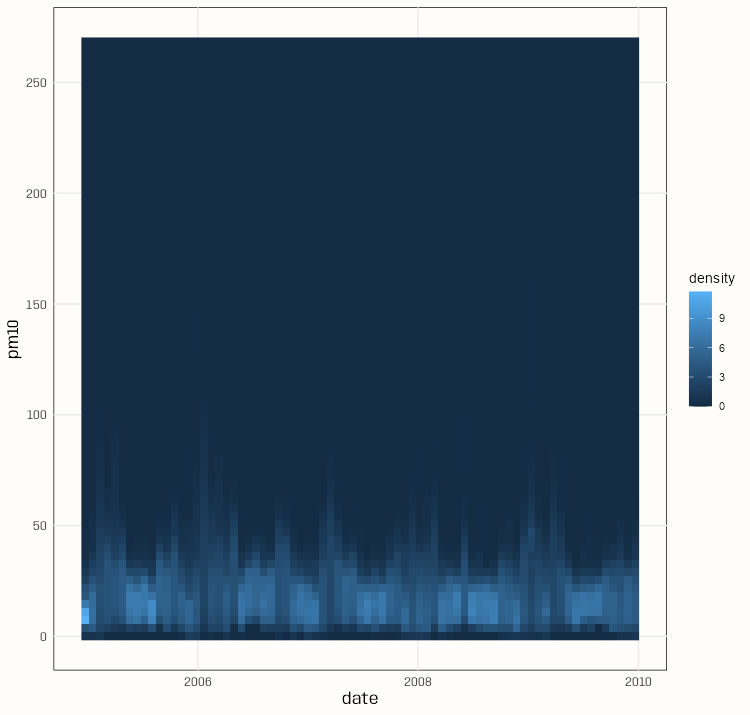

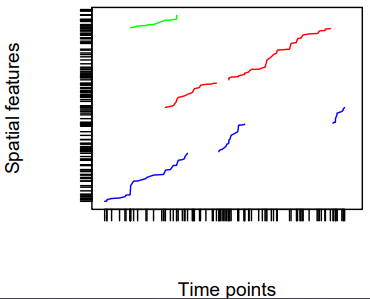

Code

pacman::p_load( spacetime, dplyr, gglinedensity, ggplot2 ) data(air) rural <- STFDF( sp = stations, time = dates, data = data.frame(PM10 = as.vector(air)) ) rr <- rural[,"2005::2010"] # remove station ts w/all NAs unsel <- which(apply( as(rr, "xts"), 2, function(x) all(is.na(x))) ) r5to10 <- rr[-unsel,] pm10_tbl <- as_tibble(as.data.frame(r5to10)) |> rename(station = sp.ID, date = time, pm10 = PM10) |> mutate(date = as.Date(date)) |> select(date, station, pm10) summary(pm10_tbl) #> date station pm10 #> Min. :2005-01-01 DESH001: 1826 Min. : 0.560 #> 1st Qu.:2006-04-02 DENI063: 1826 1st Qu.: 9.275 #> Median :2007-07-02 DEUB038: 1826 Median : 13.852 #> Mean :2007-07-02 DEBE056: 1826 Mean : 16.261 #> 3rd Qu.:2008-10-01 DEBE032: 1826 3rd Qu.: 20.333 #> Max. :2009-12-31 DEHE046: 1826 Max. :269.079 #> (Other):85822 NA's :21979 ggplot( pm10_tbl, aes(x = date, y = pm10, group = station)) + stat_line_density( bins = 75, drop = FALSE, na.rm = TRUE) + scale_y_continuous(breaks = seq.int(0, 250, 50)) + theme_notebook()- With a bunch of time series, it’s difficult to distinguish a primary trend to the data (e.g. in a spaghetti line chart). This density gives a sense of the seasonality and the trend of most of the locations.

- The summary says the median is around 14 and the max is around 270.

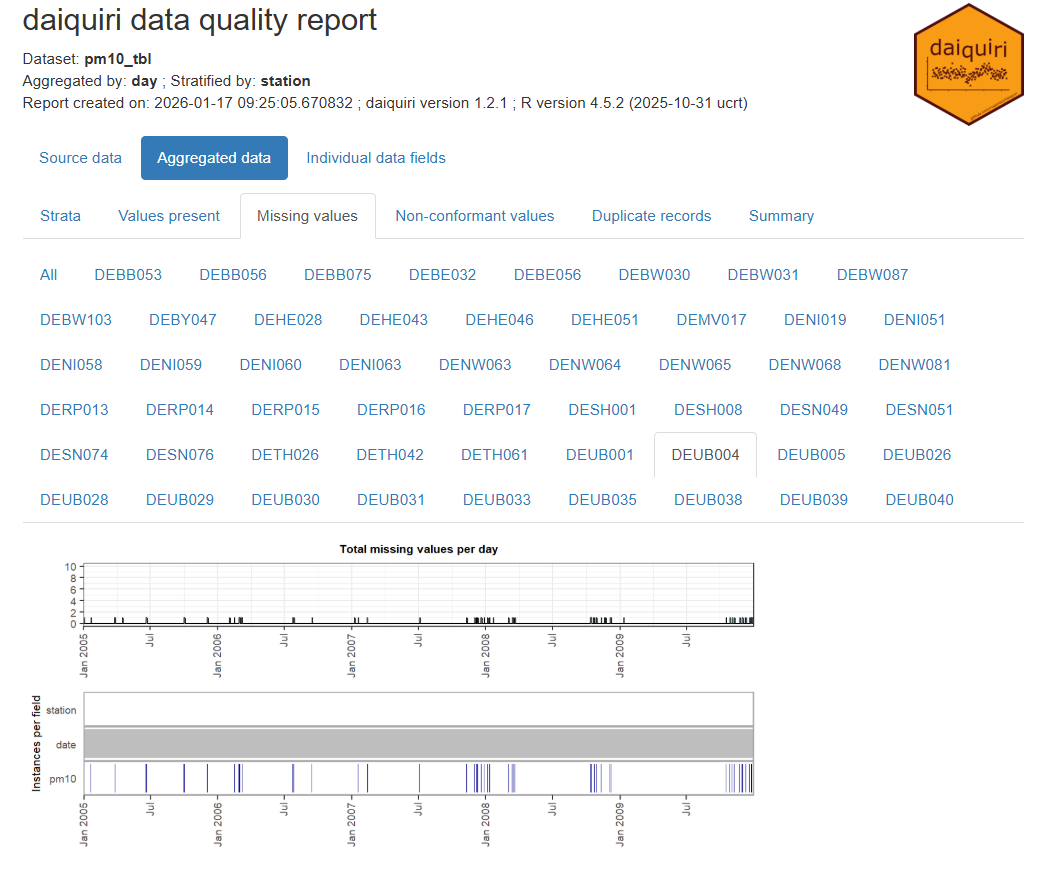

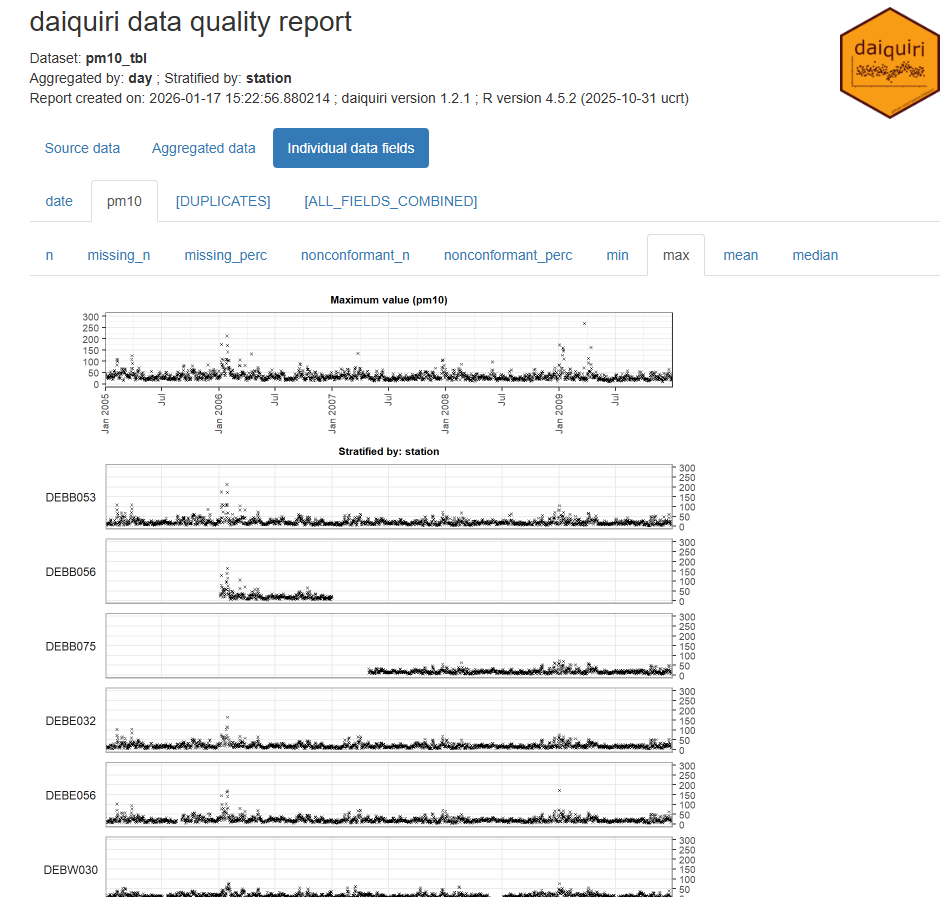

Example: {daiquiri}

Code

library(spacetime); library(dplyr); library(daiquiri) data(air) rural <- STFDF( sp = stations, time = dates, data = data.frame(PM10 = as.vector(air)) ) rr <- rural[,"2005::2010"] # remove station ts w/all NAs unsel <- which(apply( as(rr, "xts"), 2, function(x) all(is.na(x))) ) r5to10 <- rr[-unsel,] pm10_tbl <- as_tibble(as.data.frame(r5to10)) |> rename(station = sp.ID, date = time, pm10 = PM10) |> mutate(date = as.Date(date)) |> select(date, station, pm10) fts <- field_types( station = ft_strata(), date = ft_timepoint(includes_time = FALSE), pm10 = ft_numeric() ) daiq_pm10 <- daiquiri_report( pm10_tbl, fts )- Shows missingness and basic descriptive statistics over time for each station

- Note that if your data is daily and there’s only 1 measurement per day, then all these statistics will the same (duh, but one time I forgot and thought the package was broken)

- Shows missingness and basic descriptive statistics over time for each station

Temporal Dependence

Check characteristics of autocorrelation. Can the analysis be done in a purely spatial manner (a purely spatial model for each time step) or is adding a temporal aspect necessary?

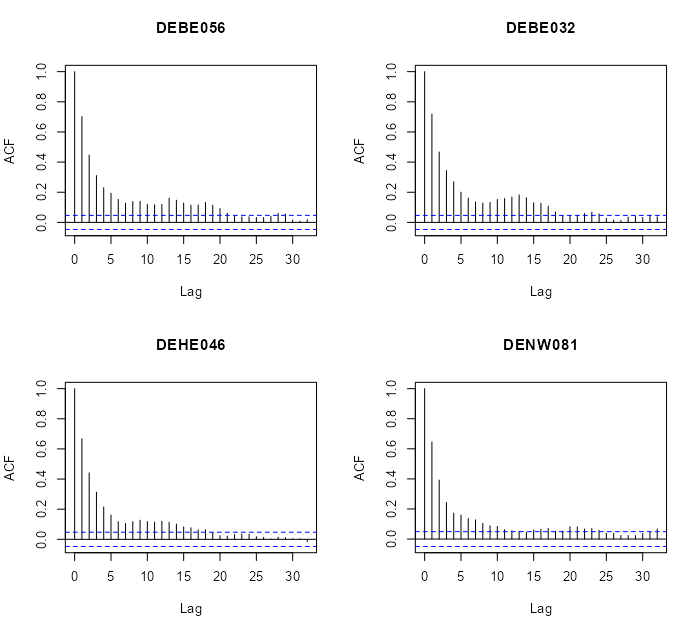

Autocorrelation Function (ACF)

- For each location, is there correlation between time \(t\) and lag \(t + h\)

- Does autocorrelation rapidly or gradually decrease?

- If gradually, then the series isn’t stationary and probably needs differencing (See EDA, Time Series >> Stationarity)

- Is there a scalloped shape to autocorrelation?

- If so, it might need seasonal differencing.

- At which time lag (max, avg) does autocorrelation become insignificant?

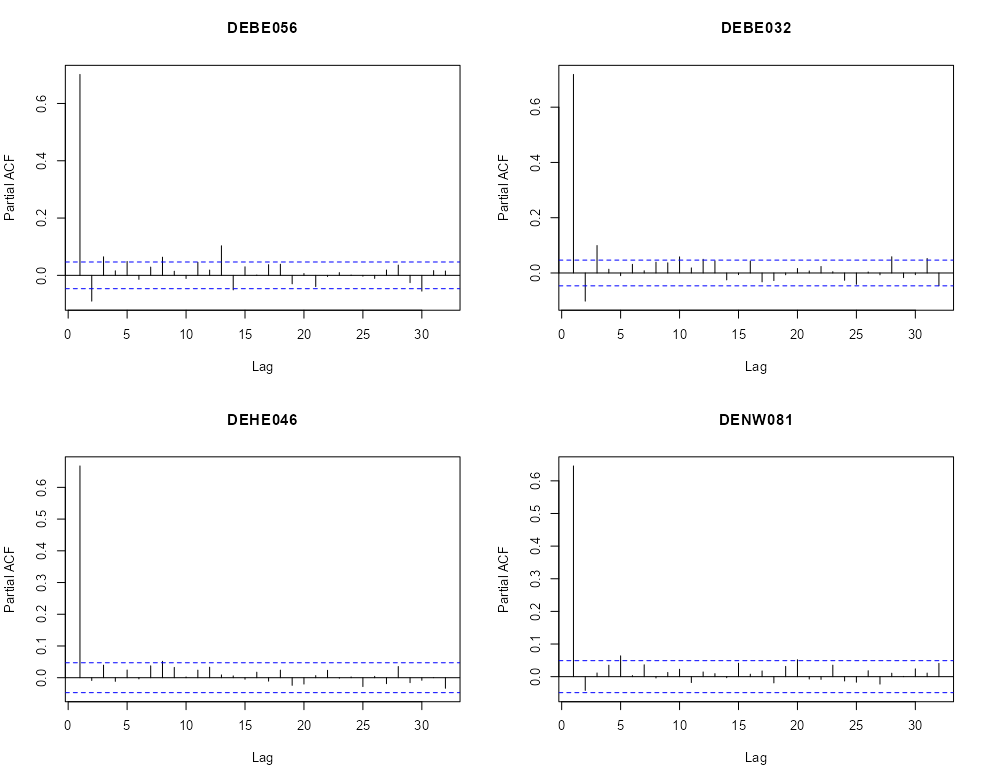

Partial Autocorrelation Function (PACF)

- Are there significant spikes in the PACF?

- Could indicate the frequency of the seasonality?

- Are there significant spikes in the PACF?

Cross-Correlations

- For each pair of locations, is there autocorrelation between location \(a\) at time \(t\) and location \(b\) at time \(t + h\)

- Cross-correlations can be asymmetric and they do not have to 1 at lag 0 like autocorrelations

- If you’re looking at rainfall at two locations, strong correlation when upstream location A leads downstream location B by 2 hours, but weak correlation when B “leads” A, tells you about the direction of storm movement and typical travel time.

- The strength of the asymmetry itself (how different the two plots look) can indicate how strong or consistent these directional relationships are in your data.

- Potential Meaning Behind Strong Asymmetry:

- Directional or causal relationships: If the cross-correlation is stronger when A leads B (positive lags in A vs B plot) than when B leads A, this suggests A might influence B more than the reverse. This doesn’t prove causation, but it’s often consistent with one variable driving changes in the other.S

- Different response times: The asymmetry can reveal that one location responds to shared drivers faster than the other, or that the propagation time of some influence differs depending on direction.

- Lead-lag relationships: Strong asymmetry with a clear peak at a non-zero lag indicates one series systematically precedes the other, which can be important for forecasting or understanding the physical mechanisms at play.

- Is there a approximate distance between many pairs of locations at which autocorrelation is insignificant?

Pooled Temporal Variogram

- A pooled temporal variogram is computed by holding space fixed and pooling squared temporal differences across spatial locations.

- It can be used with spatio-temporal data to estimate the strength of temporal dependence of various time differences.

- We can also use to get reasonable starting values for the time portions of spatio-temporal variogram models (e.g. separable, metric, product-sum, etc.)

- Let \(Y_{s,t}\) denote the observation at location \(s = 1,\dots,S\) and time \(t = 1,\dots,T\).

- The pooled estimator is:

\[ \hat{\gamma}(h_t) = \frac{1}{2 N_k(h_t)} \sum_{k=1}^{K} \sum_{s=1}^{S} \left( Y_{s,t} - Y_{s,t+u} \right)^2 \]- \(h_t\) is a temporal bin

- \(N_k(h_t)\) is the number of valid (not NA) time difference pairs in that temporal bin

- \(K\) is the number of time difference pairs

- \(S\) is number of spatial locations

- \(u\) is temporal separation

Example 1: PM10 Pollution ({gstat} vignette, section 2)

Set-Up

pacman::p_load( spacetime, stars, sf, dplyr, ggplot2 ) data(air) # get rural location time series from 2005 to 2010 rural <- STFDF( sp = stations, time = dates, data = data.frame(PM10 = as.vector(air)) ) rr <- rural[,"2005::2010"] # remove station ts w/all NAs unsel <- which(apply( as(rr, "xts"), 2, function(x) all(is.na(x))) ) r5to10 <- rr[-unsel,]- r5to10 is a STFDF (full grid) object

r5to10@spis a SpatialPoints ({sp}) class object with location names and coordinates

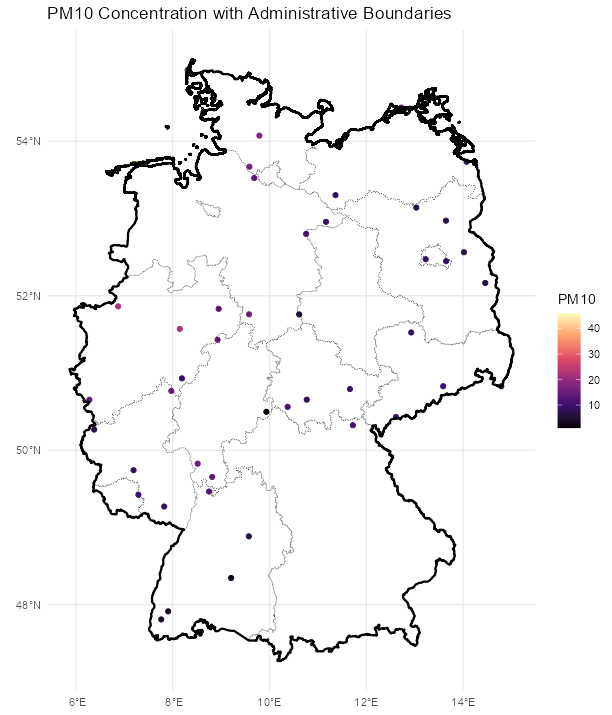

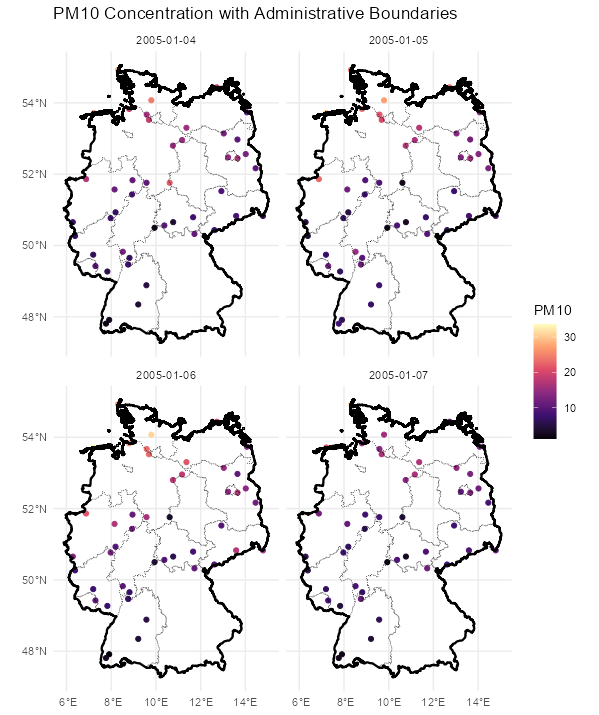

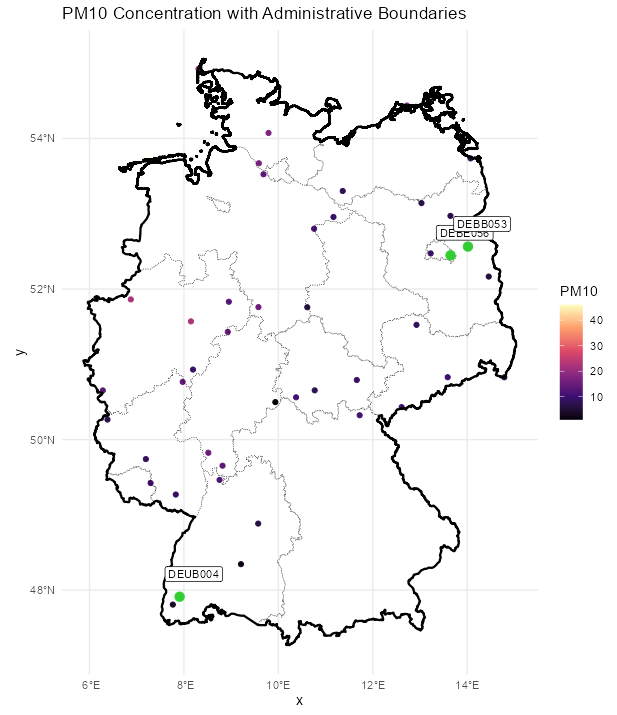

Map

Code

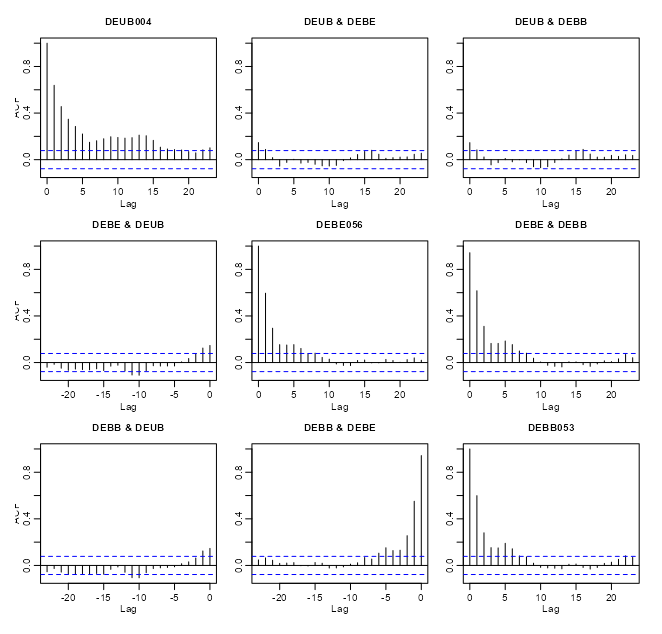

stars_r5to10 <- st_as_stars(r5to10) # stars has dplyr methods plot_slice <- slice(stars_r5to10, index = 3, # 3rd time step, so a location doesn't have NA along = "time") # country boundary de_sf <- st_as_sf(DE) # states (provinces) boundaries nuts1_sf <- st_as_sf(DE_NUTS1) ggplot() + # location points geom_stars( data = plot_slice, aes(color = PM10), fill = NA) + scale_color_viridis_c( option = "magma", na.value = "transparent") + # states geom_sf( data = nuts1_sf, fill = NA, color = "black", size = 0.2, linetype = "dotted") + # country geom_sf( data = de_sf, fill = NA, color = "black", size = 0.8) + # Ensures coordinates align correctly coord_sf() + labs( title = "PM10 Concentration with Administrative Boundaries", fill = "PM10" ) + theme_minimal() # facet multiple time steps plot_slices <- slice(stars_r5to10, index = 4:7, along = "time") plot_slices_sf <- st_as_sf(plot_slices, as_points = TRUE) plot_slices_long <- plot_slices_sf |> pivot_longer(cols = !sfc, names_to = "time", values_to = "PM10") ggplot() + geom_sf( data = plot_slices_long, aes(color = PM10)) + scale_color_viridis_c( option = "magma", na.value = "transparent") + geom_sf( data = nuts1_sf, fill = NA, color = "black", size = 0.2, linetype = "dotted") + geom_sf( data = de_sf, fill = NA, color = "black", size = 0.8) + facet_wrap(~time) + coord_sf() + labs( title = "PM10 Concentration with Administrative Boundaries", color = "PM10" ) + theme_minimal()# select locations 4, 5, 6, 7 rn = row.names(r5to10@sp)[4:7] par(mfrow=c(2,2)) for (i in rn) { x <- na.omit(r5to10[i,]$PM10) acf(x, main = i) }- There does seem to be a gradual-ness and scalloped pattern with these locations.

- Looks like at around lag 20, autocorrelation is not significant for most of these locations

par(mfrow=c(2,2)) for (i in rn) { x <- na.omit(r5to10[i,]$PM10) pacf(x, main = i) }- We see one or two significant spikes at each location, but nothing that would indicate a consistent seasonality among the locations.

# coerce to xts class xts_pm10 <- as(r5to10, "xts") # extract numeric cols mat_pm10 <- zoo::coredata(xts_pm10) # find and remove cols with NAs > 20% na_cols <- colnames(mat_pm10)[colMeans(is.na(mat_pm10)) > 0.20] mat_pm10_nacols <- mat_pm10[, !colnames(mat_pm10) %in% na_cols] mat_pm10_clean <- na.omit(mat_pm10_nacols) # all data acf(mat_pm10_clean) # vs "DEUB004" no_ac_locs <- c("DEUB004", "DEBE056", "DEBB053") mat_pm10_naac <- mat_pm10_clean[, no_ac_locs] acf(mat_pm10_naac)- r5to10 is a STFDF (full grid) object. It’s coerced, using

as, into a xts object. Since it’s now a multivariate time series object,acfwill give you cross-correlations. - From the acf of all the data, there were a couple interesting locations that had very little cross-correlation between them.

- When running

acffor a fairly large number of locations there will be a large number of charts (due to all the combinations). After one chart is rendered, in the R console, it’ll ask you to hit enter before it will render the next chart.- Note that within the cross-correlation charts, the titles of some of the location names get cut off.

If there is no or little autocorrelation between a pair of locations, is it largely because there’s a large distance between those locations? Maybe this can give a hint about the appropriate neighborhood size or area

Distance Matrix

# select low cross-corr locations and random locations # indices for the low cross-corr locations no_ac_idx <- which(row.names(r5to10@sp) %in% no_ac_locs) # indices for the column names (locations) of the cleaned matrix mat_clean_idx <- which(row.names(r5to10@sp) %in% colnames(mat_pm10_clean)) # sample 5 location indices that aren't low cross-corr locations mat_clean_idx_samp <- sort(sample(mat_clean_idx[-no_ac_idx], 5)) # combine sample indices and low cross-corr indices mat_clean_idx_comb <- c(no_ac_idx, mat_clean_idx_samp) # convert the SpatialPoints (sp) to sf sf_locs <- st_as_sf(r5to10[mat_clean_idx_comb,]@sp) # pairwise distances (in meters for geographic coordinates) mat_dist_sf <- st_distance(sf_locs) # convert to kilometers mat_dist_sf_km <- round(units::set_units(mat_dist_sf, km), 2) colnames(mat_dist_sf_km) <- row.names(r5to10[mat_clean_idx_comb,]@sp) rownames(mat_dist_sf_km) <- row.names(r5to10[mat_clean_idx_comb,]@sp) mat_dist_sf_km #> Units: [km] #> DEBE056 DEBB053 DEUB004 DEBE056 DETH026 DEUB004 DEBW031 DENW068 #> DEBE056 0.00 28.07 648.60 235.43 357.82 541.62 198.99 557.63 #> DEBB053 28.07 0.00 674.84 256.26 374.67 569.64 221.21 585.50 #> DEUB004 648.60 674.84 0.00 441.77 660.90 209.86 579.71 173.85 #> DEBE056 235.43 256.26 441.77 0.00 458.62 393.98 292.91 396.71 #> DETH026 357.82 374.67 660.90 458.62 0.00 467.91 173.13 500.94 #> DEUB004 541.62 569.64 209.86 393.98 467.91 0.00 420.84 36.08 #> DEBW031 198.99 221.21 579.71 292.91 173.13 420.84 0.00 446.54 #> DENW068 557.63 585.50 173.85 396.71 500.94 36.08 446.54 0.00 # using sp mat_dist_sp <- round(sp::spDists(r5to10[mat_clean_idx_comb,]@sp), 2) colnames(mat_dist_sp) <- row.names(r5to10[mat_clean_idx_comb,]@sp) rownames(mat_dist_sp) <- row.names(r5to10[mat_clean_idx_comb,]@sp)- The 3rd column (DEUB004) and first two rows (DEBE056, DEBB053) shows the distances between the low cross-correlation locations. The other locations are included for context.

- The distances for those low cross-correlations location pairs do seem to be quite a bit larger than the other 5 randomly sampled locations when paired with DEUB004. So the low cross-correlations are likely due to larger spatial distances between the locations.

- Might be interesting to check the cross-correlation between DEUB004 and DETH026 and maybe DEBW031 just to see how low those cross-correlations are in comparison.

- The {sp} and {sf} numbers are slightly different, because {sp} uses spherical and {sf} uses elliptical distances. The elliptical should be more accurate, but either should be fine for most applications (fraction of a percentage difference)

Map

Code

labeled_points <- st_as_sf(plot_slice, as_points = TRUE) |> mutate(station = rownames(r5to10@sp@coords)) |> filter(station %in% c("DEUB004", "DEBE056", "DEBB053")) ggplot() + # location points geom_stars( data = plot_slice, aes(color = PM10), fill = NA) + scale_color_viridis_c( option = "magma", na.value = "transparent") + # states geom_sf( data = nuts1_sf, fill = NA, color = "black", size = 0.2, linetype = "dotted") + # country geom_sf( data = de_sf, fill = NA, color = "black", size = 0.8) + # Ensures coordinates align correctly coord_sf() + # color labelled points differently geom_sf( data = labeled_points, color = "limegreen", size = 3, shape = 21, fill = "limegreen") + geom_sf_label( data = labeled_points, aes(label = station), nudge_x = 0.3, nudge_y = 0.3, size = 3) + labs( title = "PM10 Concentration with Administrative Boundaries", fill = "PM10") + theme_minimal()- Pretty much on the other side of the country, but there are locations further away. Again, it’d be interesting to look at the cross-correlations between some of the pairs of locations that are just as far or farther away.

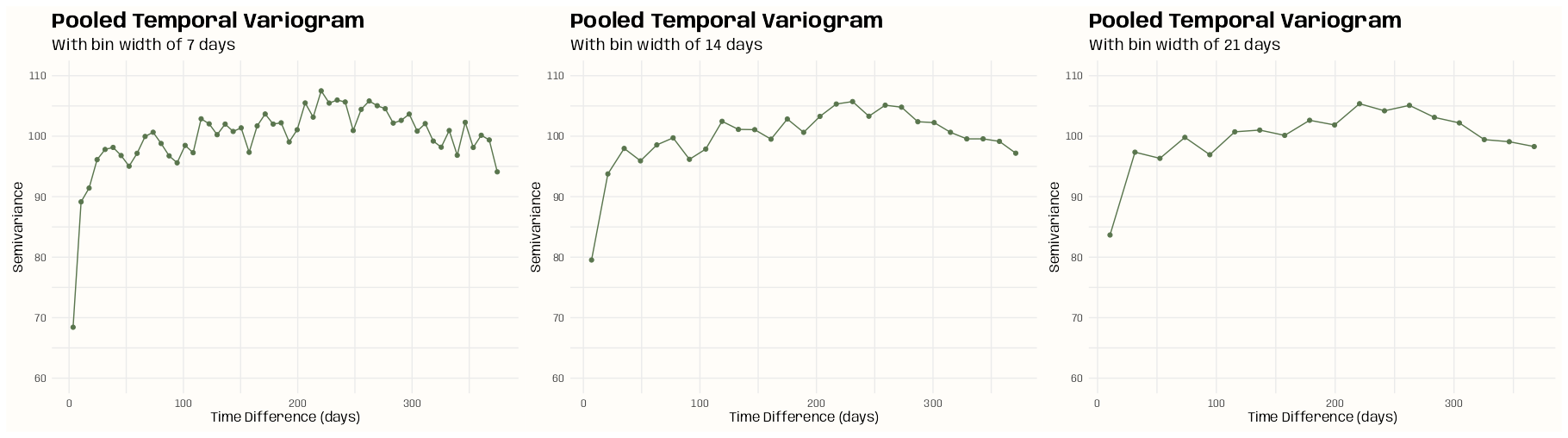

Example 2: Pooled Temporal Variogram

This is the PM10 air pollution dataset for Germany that’s from {spacetime} and used in many of my examples.

The goal is to find starting values for temporal

vgmportions spatio-temporal variogram models.pacman::p_load( ebtools, # pooled_temporal_variogram ggplot2, patchwork, gstat ) data(air, package = "spacetime") keep_cols <- dates >= as.Date("2005-01-01") & dates <= as.Date("2010-12-31") air_sub <- air[, keep_cols] # Remove locations with all NAs keep_rows <- rowSums(!is.na(air_sub)) > 0 air_sub <- air_sub[keep_rows, ] # add dates as column names keep_dates <- as.character(dates[keep_cols]) colnames(air_sub) <- keep_datespooled_temporal_variogramis from my personal package and requires a space-time matrix with date or datetime strings as column names.

ls_vario_time <- purrr::map( c(7, 14, 21), # 1wk, 2wks, 3wks \(x) { pooled_temporal_variogram( Y = air_sub, bin_width = x, max_time_diff = 375 # slightly more than a year in case there's noise ) } ) ls_plots <- purrr::map2( ls_vario_time, c(7, 14, 21), \(vario_obj, binwidth) { ggplot(vario_obj, aes(x = dist, y = gamma)) + geom_point(color = "#59754D") + geom_line(color = "#59754D") + expand_limits(y = 60:110) + labs( x = "Time Difference (days)", y = "Semivariance", title = "Pooled Temporal Variogram", subtitle = glue::glue("With bin width of {binwidth} days") ) + theme_notebook() + theme(panel.grid.minor = element_line()) } ) ls_plots[[1]] + ls_plots[[2]] + ls_plots[[3]]- tl;dr MY RANGE ESTIMATION WAS BAD. The main issue I think was that I didn’t extend the y-axis to zero in my plots which zoomed me into the data. It caused me to over-interpret the pattern which led me to estimate a larger range. Turns out that the variogram model sees the data as FLAT which leads to a much smaller range. When you see the plots in the next section you can kind of see where it’s coming from, and honestly with air pollution, a small range makes more intuitive sense to me.

- My nugget and sill estimations (and some other stuff) were pretty good at least (for some models).

- I’m leaving this interpretation here, because it might be helpful to look back upon for when there is an actual pattern in my data.

- Using a bin width 7 is best for nugget estimation and initial detection of any patterns (e.g. seasonality)

- My nugget estimation: ~68 units

- So probably some micro-scale variation or measurment error present

- My nugget estimation: ~68 units

- Using a bin width 14 and 21 is best for sill and range estimation

- Refinement of interpretation of any patterns

- Sill estimation: ~103 units

- Range estimation options:

- Use the bump: ~220 days

- Treat the bump as an anomaly: ~120 days

- The rapid rise and leveling indicates strong short-term temporal dependence

- The bump could indicate some seasonality. It begins at around 200 days and lasts until around 300 days.

- The (temporal) variogram assumes stationarity. So, if strong enough, it could substantially bias the estimation.

- Perhaps some seasonal differencing may be useful

- Internally subtract location-wise mean or seasonal mean (rows in the matrix)

- The nugget-sill ratio: 68/103 = 0.66 which is quite high

- Interpretation:

- High day-to-day variability

- Since roughly two-thirds of the total variance is unstructured at the resolution of the sampling

- Weak persistence after short lags

- i.e. variable de-autocorrelates quickly after a 2 or 3 weeks

- This is realistic for air pollution

- High day-to-day variability

- Reasons

- Pollution levels are driven by episodic events (traffic, wind shifts, industrial emissions, weather fronts)

- Day-to-day meteorological forcing is highly variable and not strongly autocorrelated

- PM10 responds quickly to local conditions and doesn’t “persist” the way a slower variable like soil organic matter or groundwater depth might

- Interpretation:

- The dip after ~275 days suggests one of:

- Finite sample noise (most likely)

- Seasonality (annual structure)

- Potentially correct as the bump is at the tail

- Not enough pairs

- There are more than enough, so this ain’t it

Without Nugget

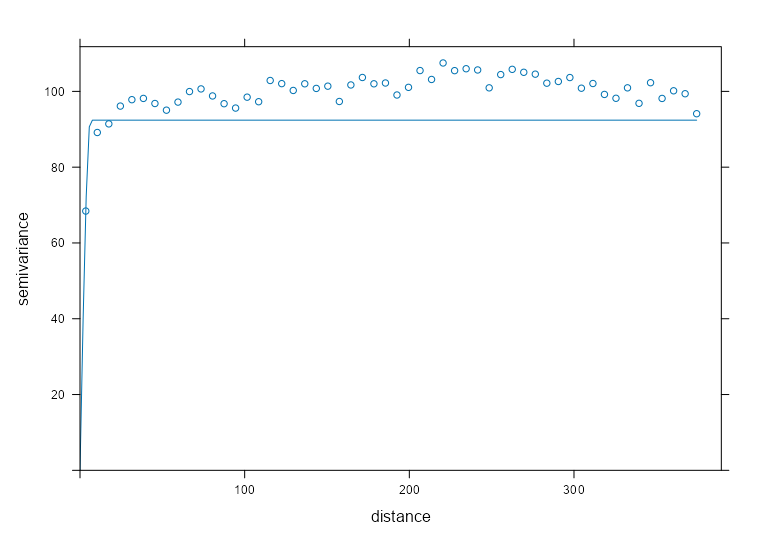

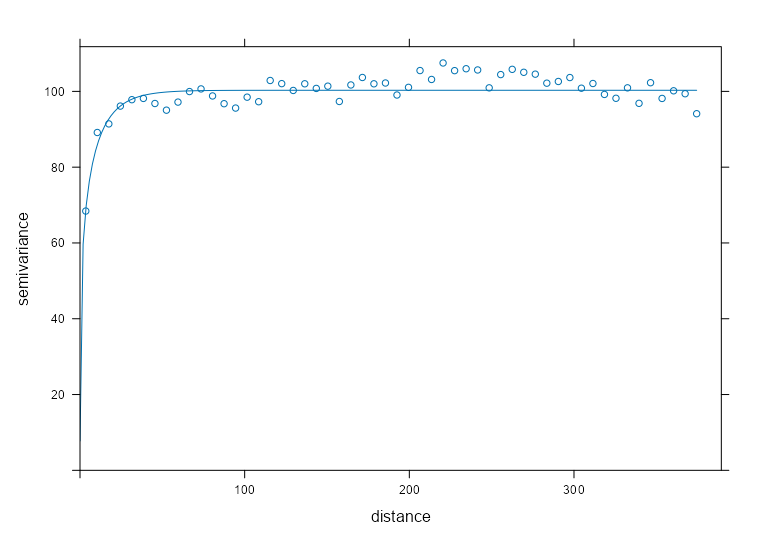

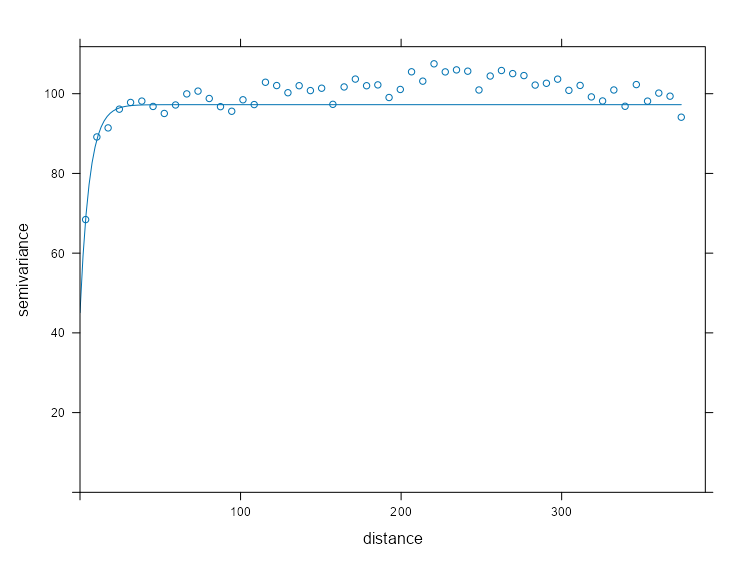

mod_vario_time_exp <- fit.variogram( object = ls_vario_time[[1]], model = vgm( model = "Exp", psill = 35, # units; 103-68 range = 120 # days ) ) mod_vario_time_exp #> model psill range #> 1 Exp 93.56833 2.669963 plot( x = ls_vario_time[[1]], mod_vario_time_exp ) mod_vario_time_sph <- fit.variogram( object = ls_vario_time[[1]], model = vgm( model = "Sph", psill = 35, # units; 103-68 range = 120 # days ) ) mod_vario_time_sph #> model psill range #> 1 Sph 92.40597 6.379134 plot( x = ls_vario_time[[1]], mod_vario_time_sph ) mod_vario_time_mat <- fit.variogram( object = ls_vario_time[[1]], model = vgm( model = "Mat", psill = 35, # units; 103-68 range = 120, # days, kappa = 0.12 ) ) mod_vario_time_mat #> model psill range kappa #> 1 Mat 100.2906 14.42514 0.12 plot( x = ls_vario_time[[1]], mod_vario_time_mat )- I used the finer bin width (7 days) variogram, because there are still plenty of time difference pairs for semivariance estimation and there’s no danger of overfitting these models.

- There are many models avaiable in gstat, but a lot are for specialized situations and the rest errored or didn’t converge. I didn’t investigate why some errored or didn’t converge, so I just ended up with these three.

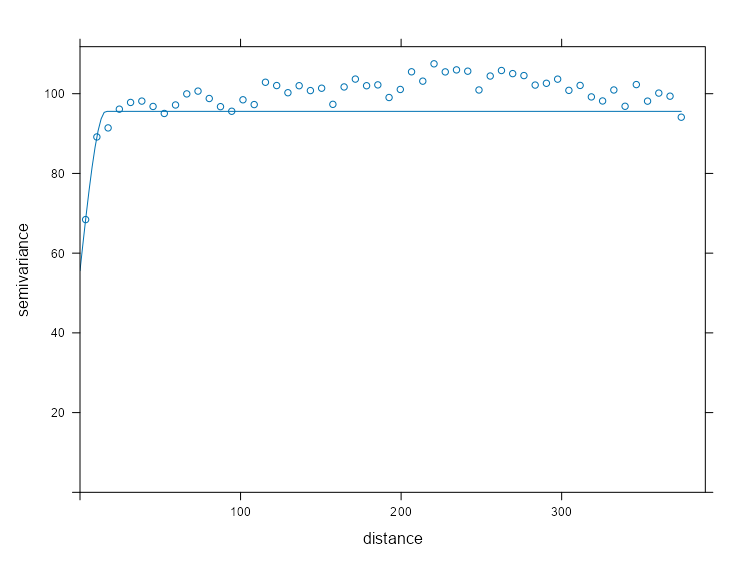

With Nugget

mod_vario_time_exp_nug <- fit.variogram( object = ls_vario_time[[1]], model = vgm( model = "Exp", psill = 35, # units; 103-68 range = 2, # days nugget = 68 ) ) mod_vario_time_exp_nug #> model psill range #> 1 Nug 45.06836 0.000000 #> 2 Exp 52.17817 5.894366 plot( x = ls_vario_time[[1]], mod_vario_time_exp_nug, ) mod_vario_time_sph_nug <- fit.variogram( object = ls_vario_time[[1]], model = vgm( model = "Sph", psill = 35, # units; 103-68 range = 120, # days nugget = 68 ) ) mod_vario_time_sph_nug #> model psill range #> 1 Nug 55.59087 0.00000 #> 2 Sph 39.97869 16.10447 plot( x = ls_vario_time[[1]], mod_vario_time_sph_nug ) mod_vario_time_mat_nug <- fit.variogram( object = ls_vario_time[[1]], model = vgm( model = "Mat", psill = 35, # units; 103-68 range = 120, # days, kappa = 0.12, nugget = 68 ) ) mod_vario_time_mat_nug #> model psill range kappa #> 1 Nug 0.0000 0.00000 0.00 #> 2 Mat 100.2906 14.42514 0.12 plot( x = ls_vario_time[[1]], mod_vario_time_mat_nug )- words

Spatial Dependence

Is there meaningful spatial correlation at all (relative to noise)?

- Spatio-temporal variograms can appear structured even when spatial dependence is negligible—especially when temporal correlation is strong. So, we need to test whether spatial dependence exits independently.

- If there were no spatial correlation, then for almost all spatial lags (i.e. pure nugget behavior), semi-variance is constant.

- With spatial correlation, there should be a monotonic increase as distance increases which eventually plateaus.

- Tells us that spatial dependence is not drowned out by temporal variability

On what distance scale does spatial correlation operate?

- At what distance does the variogram level off?

- Realize the empirical range (calculated in the variogram model) and the practical range (using your eyes) are two different things.

- In general does this distance suggest a State-wide spatial dependence? County-wide? Region-wide? etc.

- At what distance does the variogram level off?

Is the spatial structure smooth or erratic?

- Can one curve fit the data well or are there groups of bins that stand out as not being fit well by the model curve.

- Does monotonicity of the bins fail? (i.e. a bin at greater distance than another but having a smaller semi-variance)

- Try spatial detrending (e.g. regress on coordinates, covariates) or temporal detrending can restore a monotone variogram.

- If variance or mean changes over time and you pool time slices, then differencing in time (or demeaning by time) can stabilize variance. Then, the short-lag spatial structure can become clearer.

Is fitting a full spatio-temporal variogram likely to succeed?

- Flat variogram → Don’t bother with spatial-temporal modeling when there’s no need for even spatial modeling.

- Extremely short range → Metric models likely degenerate.

- Wild instability → Spatio-Temporal fitting will be numerically meaningless. (too much noise → too much uncertainty → predictions essentially meaningless)

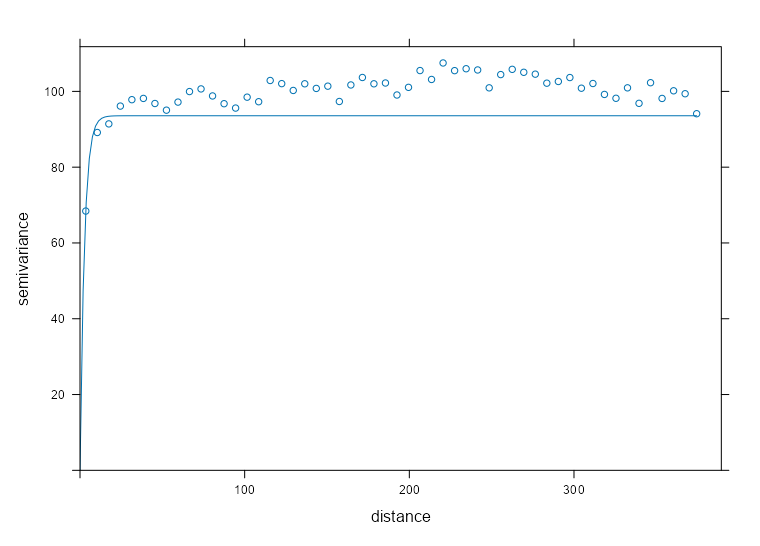

Example:

- The data, r5to10, is PM10 measurements across 53 measurement stations in Germany. See EDA >> Autocorrelation >> Example 1 for details on this data.

- Pooled spatial variograms are analyzed. Spatial dependence is calculated per sampled time instance and pooled across all sampled time instances.

- Bootstrap distributions for the partial sill and range are calculated. These could give us a potential range of starting values if we use the same model (exponential) in the spatio-temporal variogram.

pacman::p_load( spacetime, gstat, tidyverse, futurize ) # sample 100 time instances (days) vec_time <- sample( x = dim(r5to10)[2], size = 100 # also used 300 ) ls_samp <- lapply( vec_time, function(i) { x = r5to10[,i] x$time_index = i rownames(x$coords) = NULL x } ) spdf_samp <- do.call( what = rbind, args = ls_samp )- 100 time instances (days) are sampled

- For each time instance, the STFDF is subsetted by that day. Then that day is added to a new variable, time_index.

- Each element of ls_samp is a SpatialPointsDataFrame and

rbindcombines the elements into one SpatialPointsDataFrame

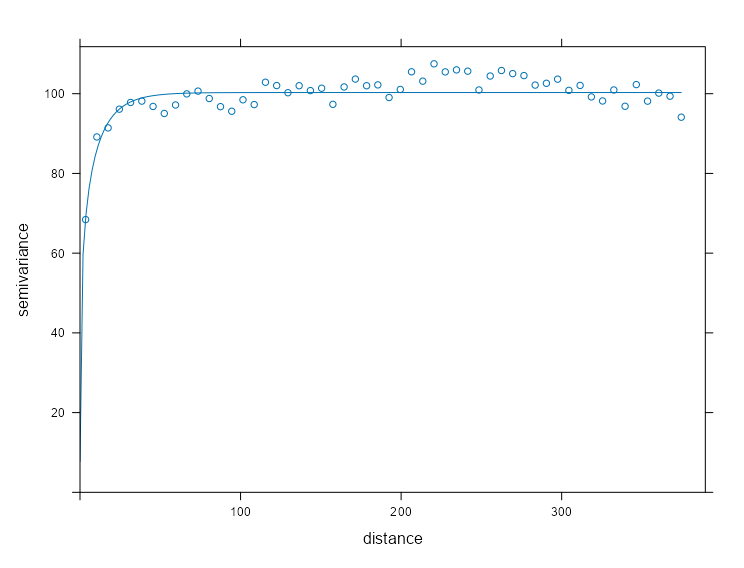

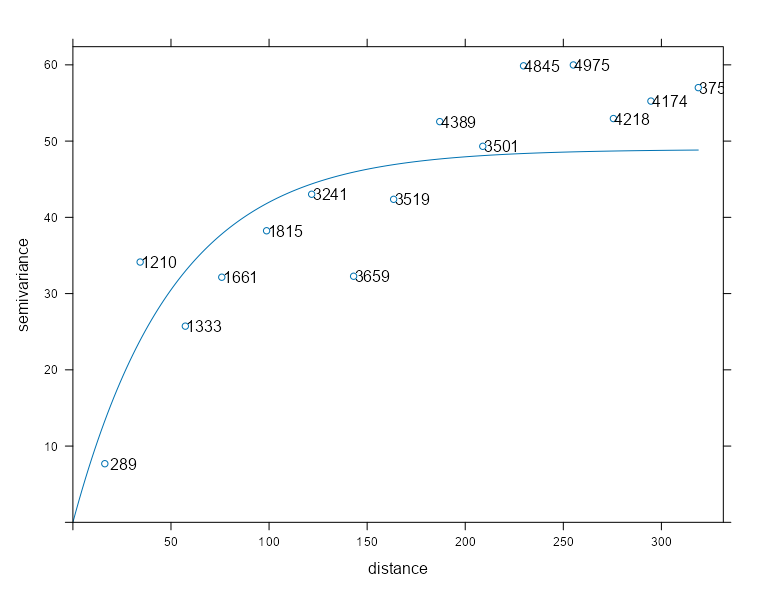

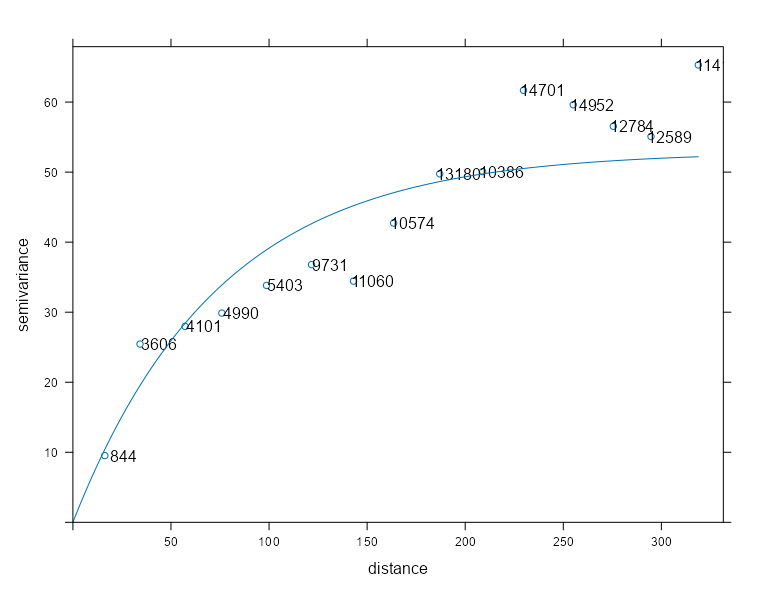

vario_samp <- variogram( object = PM10 ~ time_index, locations = spdf_samp[!is.na(spdf_samp$PM10),], dX = 0 ) mod_vario_samp_exp <- fit.variogram( object = vario_samp, model = vgm( psill = 100, model = "Exp", range = 200 ) ) mod_vario_samp_exp #> model psill range #> 1 Exp 48.92291 51.20898 plot( x = vario_samp, mod_vario_samp_exp, plot.numbers = TRUE )- The spatial variogram on the left uses 100 time slices (i.e. 100 days) and the one on the right uses 300.

- The one on the left looks more unstable in the region (small distance pairs) where the range is estimated.

- Monotonicity is broken where the third bin has a lower semi-variance than the second bin.

- There is a large jump in semi-variance between the first and second bin.

- In the one on right, monotonicity is restored and a smaller jump from bin 1 to bin 2 which results in a flatter fitted curve.

- dX = 0 because including pairs from different time slices might have these effects:

- If temporal correlation is weak, short-distance bins inflate

- The estimated “spatial” range shrinks artificially

- The sill and nugget lose spatial interpretation

- There are 53 locations, so

choose(53, 2)says there 1,378 location pairs per time slice. Therefore, sampling 100 time instances means there are 13,780 pairs overall used to calculate this empirical variogram. - While this seems like a lot of data, it doesn’t fundamentally give us more spatial information about the area. Whether we sample 100 or use all the time slice to calculate the empirical variogram, the salient spatial variable is the number of locations which is just 53.

- More time slices gives less variance (smoother line) to our model’s estimate of the psill and range, but doesn’t make it more accurate in terms of true “population” values. To increase the accuracy, we’d need more locations taking PM10 measurements.

- After fitting variograms with a few different amounts of sampled time slices/instances a number of times, the variograms were substantially different — making it difficult to gain a feel for the partial sill and range parameters. Applying the bootstrap should give a better sense for a range of starting values for each of those parameters.

- From the autocorrelation EDA example, there does seem to be some pretty strong autocorrelation present, so using the block version of bootstrapping makes sense. Probably could make blocks up to around 21 days judging by the ACFs, but I just went with 14 days here.

- Note that cross-correlations are more of spatio-temporal calculation. Setting dX = 0, means we’re modeling spatial dependence within time slices and then pooling, so the ACF is more appropriate to base our block length off of.

Block Bootstrap the Partial Sill and Range

See Confidence and Prediction Intervals >> Bootstrapping >> Example 2: Block Bootstrap for more details on the code.

Code

# ---------- Model and Block Functions ---------- # 1estim_params_vgm <- function(idx_time_resamp, dat) { ls_dat <- lapply( idx_time_resamp, function(i) { x <- dat[, i] x$time_index <- i rownames(x@coords) <- NULL x } ) spdf <- do.call(rbind, ls_dat) spdf <- spdf[!is.na(spdf$PM10), ] vario_exp <- variogram( PM10 ~ time_index, spdf, dX = 0 ) vario_mod <- try( fit.variogram( vario_exp, vgm(psill = 100, "Exp", range = 200)), silent = TRUE ) if (inherits(vario_mod, "try-error")) return(c(NA, NA)) tibble( psill = vario_mod$psill, range = vario_mod$range ) } make_block_indices <- function(n_time, time_slices, block_length, n_samples) { mat_idxs <- matrix(NA, nrow = n_samples, ncol = time_slices) 2 for (r in seq_len(n_samples)) { idx <- integer(0) 3 while (length(idx) < time_slices) { start <- sample( 1:(n_time - block_length + 1), size = 1 ) idx <- c(idx, start:(start + block_length - 1)) } mat_idxs[r, ] <- idx[seq_len(time_slices)] } return(mat_idxs) } # ---------- Run it ---------- # 4 time_slices <- 300 # 300 days block_length <- 14 # 2 weeks n_samples <- 200 # 200 resamples block_idxs <- make_block_indices( n_time = dim(r5to10)[2], time_slices = time_slices, block_length = block_length, n_samples = n_samples ) plan(future.mirai::mirai_multisession, workers = 10L) tib_vario_params <- purrr::map( asplit(block_idxs, 1), \(x) { estim_params_vgm(x, dat = r5to10) } ) |> futurize() |> list_rbind() mirai::daemons(0)- 1

- The basically just functionalizes the part of the script in the previous tabs and extracts the psill and range parameters from the variogram model

- 2

- Iterates through the number of bootstrap replicates specified by n_samples

- 3

- Generates blocks until the length of the replicate reaches the fixed length (time_slices)

- 4

-

A matrix is created with

make_block_indiceswhere each row is indices of PM10 observations which are organized in blocks of 14 days. Each row of that matrix is fed intoestim_parmas_vgmwhere a variogram model is fit. The calculated psill and range parameters of the fitted model are collected in a tibble

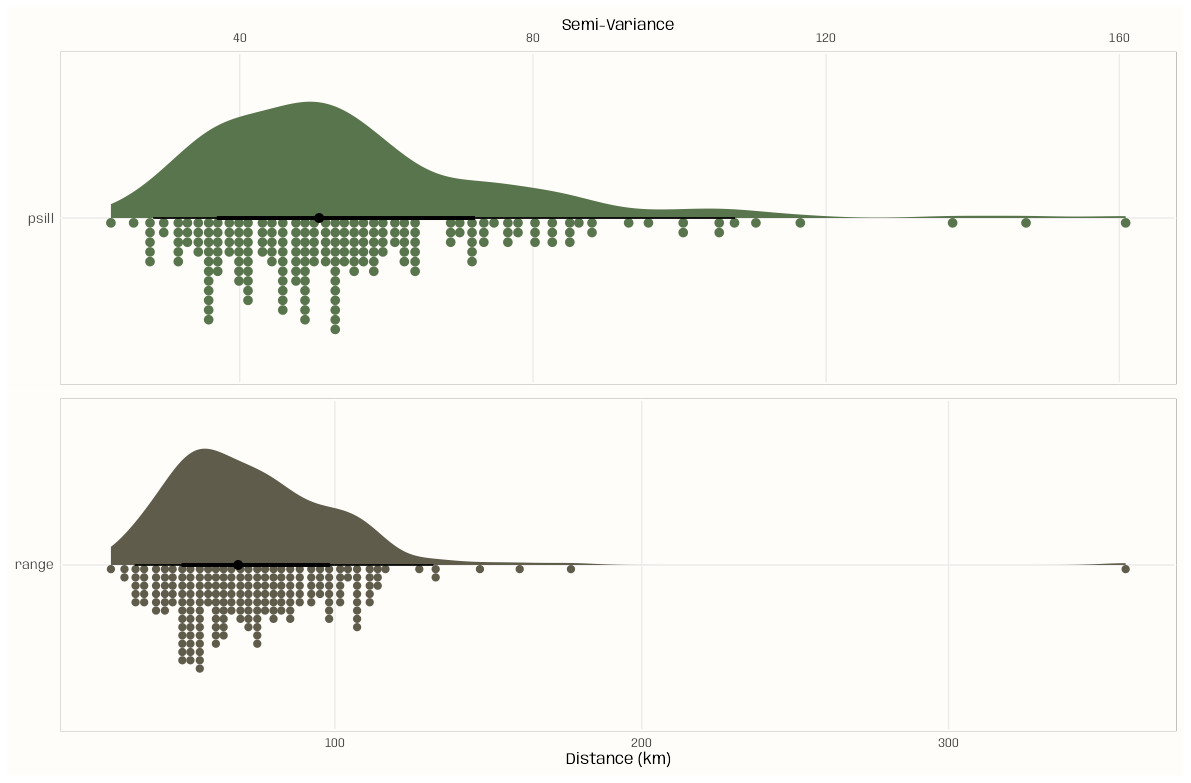

Results

summary(tib_vario_params) #> psill range #> Min. : 22.43 Min. : 27.00 #> 1st Qu.: 40.79 1st Qu.: 53.54 #> Median : 50.84 Median : 68.48 #> Mean : 55.30 Mean : 73.89 #> 3rd Qu.: 62.64 3rd Qu.: 87.91 #> Max. :160.85 Max. :357.72 sd(tib_vario_params$psill) #> [1] 21.50009 sd(tib_vario_params$range) #> [1] 32.32091- We have medians less than means, so skew is present

- The variance of each distribution is quite large.

Visualize

Code

library(ggdist); library(patchwork) notebook_colors <- unname(swatches::read_ase(here::here("palettes/Forest Floor.ase"))) tib_plot <- tib_vario_params |> pivot_longer(cols = everything(), names_to = "parameter") |> group_split(parameter) psill_plot <- ggplot( data = tib_plot[[1]], aes(y = parameter, x = value, fill = parameter)) + stat_slab( aes(thickness = after_stat(pdf*n)), scale = 0.7) + stat_dotsinterval( side = "bottom", scale = 0.7, slab_linewidth = NA) + scale_x_continuous(position = "top") + scale_fill_manual(values = notebook_colors[[4]]) + xlab("Semi-Variance") + guides(fill = "none") + theme_notebook( axis.title.y = element_blank(), panel.border = element_rect(color = "#FFFDF9FF", fill = "#FFFDF9FF", linewidth = 1.5)) range_plot <- ggplot( data = tib_plot[[2]], aes(y = parameter, x = value, fill = parameter)) + stat_slab( aes(thickness = after_stat(pdf*n)), scale = 0.7) + stat_dotsinterval( side = "bottom", scale = 0.7, slab_linewidth = NA) + scale_fill_manual(values = notebook_colors[[8]]) + xlab("Distance (km)") + guides(fill = "none") + theme_notebook( axis.title.y = element_blank(), panel.border = element_rect(color = "#FFFDF9FF", fill = "#FFFDF9FF", linewidth = 1.5)) psill_plot/range_plot- Both parameter distributions are right-skewed with some outliers

- So if we were to create a grid a starting values, it could be pretty wide.

- Maybe more than 300 days (out of 1826 days) for the number of sampled time instances (slices) would help, but this is likely do to there only being 53 stations taking measurements.

Kriging

Misc

Packages

- {gstat} - OG; Has idw and various kriging methods.

The added value of spatio-temporal kriging lies in the flexibility to not only interpolate at unobserved locations in space, but also at unobserved time instances.

- This makes spatio-temporal kriging a suitable tool to fill gaps in time series not only based on the time series solely, but also including some of its spatial neighbours.

A potential alternative to spatio-temporal kriging is co-kriging.

- Only feasible if the number of time replicates is (very) small, as the number of cross variograms to be modelled equals the number of pairs of time replicates.

- Co-kriging can only interpolate for these time slices, and not inbetween or beyond them. It does however provide prediction error covariances, which can help assessing the significance of estimated change parameters

The best fits of the respective spatio-temporal models might suggest different variogram families and parameters for the pure spatial and temporal ones.

Spatio-Temporal vs Purely Spatial

- By examining the spatio-temporal variogram plot, you

- Example (gstat vignette): A temporal lag of one or a few days leads already to a large variability compared to spatial distances of few hundred kilometers, implying that the temporal correlation is too weak to considerably improve the overall prediction.

- By examining the spatio-temporal variogram plot, you

For large datasets

- Try local kriging (instead of global kriging) by selecting data within some distance or by specifying nmax (the nearest n observations). (See

krigeSTbelow)

- Try local kriging (instead of global kriging) by selecting data within some distance or by specifying nmax (the nearest n observations). (See

Workflow

# calculate sample/empirical variogram vario_samp <- variogramST() # specify covariance model mod_cvar <- vgmST() # fit variogram model vario_mod <- fit.STVariogram( object = vario_samp, model = mod_cvar ) # run variogram diagnostics attr(vario_mod, "optim")$value plot(vario_mod) plot(vario_samp, vario_mod, wireframe = T)

Variogram

variogramST

- Docs

- Fits the Empirical/Experimental Variogram

- Evidently fitting this object can take a crazy amount of time even with moderately sized datasets. So, it’s recommended to utilize the parallelization option (cores)

- In this article, he used a dataset with 6734 rows, and the dude ran it overnight. He didn’t use the core argument though. It was published 2015, so it might not have been available.

- cutoff - Spatial separation distance up to which point pairs are included in semivariance estimates

- Default: The length of the diagonal of the box spanning the data is divided by three.

- tlags - Time lags to consider. Default is 0:15

- For STIDF data, the argument tunit is recommended (and only used in the case of STIDF) to set the temporal unit of the tlags.

- The number of time lags is multiplied by the number of spatial bins to get the total bins. So the fewer the better, if the situation allows it. Fewer might also reduce computation time.

- Seems like days are typical time unit is spatio-temporal data, so 15 lags might be a lot depending on what’s being measured.

- Using the ACFs to get an idea

- twindow - Controls the temporal window used for temporal distance calculations.

- This avoids the need of huge temporal distance matrices. The default uses twice the number as the average difference goes into the temporal cutoff. (I think this means twice the max of tlags)

- Reduces unnecessary pair construction

- Lowers memory use

- Therefore, speeding up computation

- The function will create time-distance pairs that aren’t necessary

- Example: STFDF

- If time = Jan 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and tlags is set to 0:3

- By default, the function will create the distance pair 1,6 even though a lag of at most 3 days is all we care about.

- Setting twindow = 3 makes sure pairs like (1,6) aren’t created.

- Example: STFDF

- For STFDF cases, setting twindow = max(tlags) makes sense because any less and not all the desired tlags pairs get created and any more is meaningless because those pairs won’t be used in the semi-variance calculations.

- For STIDF cases, maybe there’s something like Jan 3.5 which represents noon on that day and you want the pair (0, 3.5) created where max(tlags) = 3. Not sure if that pair would be included in the semi-variance calculation or not though. Might require a special tunits specification or transformation or something.

- This avoids the need of huge temporal distance matrices. The default uses twice the number as the average difference goes into the temporal cutoff. (I think this means twice the max of tlags)

- width - The width of subsequent distance intervals into which data point pairs are grouped for semivariance estimates

- Default: The cutoff is divided into 15 equal lags

- Also see Geospatial, Kriging >> Bin Width

- cores - Compute in parallel

vgmST

- Docs

- Specifies the variogram model function.

- Misc

- See Geospatial, Modeling >> Interpolation >> Kriging >> Variograms >> Terms for descriptions of sill, nugget, and range.

- For

vgm, you can just usevgm("exponential")and not worry about setting parameters like sill, nugget, etc. This might also be the case withvgmST. (See Geospatial, Models >> Interpolation >> Kriging >> Variograms>> Example 1) - For space and time arguments,

vgmis used to specify those models

- Covariance Models

- Separable

- Covariance Function: \(C_{\text{sep}} = C_s(h)C_t(u)\)

- Variogram: \(\gamma_{\text{sep}}(h, u) = \text{sill} \cdot (\bar \gamma_s (h) + \bar \gamma_t(u) - \bar\gamma_s(h)\bar\gamma_t(u))\)

- \(h\) is the spatial step and \(u\) is the time step

- \(\bar \gamma_s\) and \(\bar \gamma_t\) are standardized spatial and temporal variograms with separate nugget effects and (joint) sill of 1

vgmST(stModel = "separable", space, time, sill)- Has a strong computational advantage in the setting where each spatial location has an observation at each temporal instance (STFDF without NAs)

- Product-Sum

- Covariance Function: \(C_{\text{ps}}(h,u) = kC_s(h)C_t(u) + C_s(h) + C_t(u)\)

- With \(k \gt 0\) (Don’t confuse this with the kappa anisotropy correction below)

- Variogram:

\[ \begin{align} \gamma_{\text{ps}}(h,u) = \;&(k \cdot \text{sill}_t + 1)\gamma_s(h) + \\ &(k \cdot \text{sill}_s + 1)\gamma_t(h) -\\ &k\gamma_s(h)\gamma_t(u) \end{align} \] vgmST(stModel = "productSum", space, time, k)

- Covariance Function: \(C_{\text{ps}}(h,u) = kC_s(h)C_t(u) + C_s(h) + C_t(u)\)

- Metric

- Assumes identical spatial and temporal covariance functions except for spatio-temporal anisotropy

- i.e. Requires both spatial and temporal models use the same family. (e.g. spherical-spherical)

- Covariance Function: \(C_m(h,u) = C_{\text{joint}}(\sqrt{h^2 + (\kappa \cdot u)^2})\)

- \(C_{\text{joint}}\) says that the spatial, temporal, and spatio-temporal distances are treated equally.

- \(\kappa\) is the anisotropy correction.

- It’s in space/time units so multiplying it times the time step, \(u\), converts time into distance. This allows spatial distance and temporal “distance” to be used together in the euclidean distance calculation

- e.g. \(\kappa = 189 \frac{\text{km}}{\text{day}}\) says that 1 day is equivalent to 189 km.

- Variogram: \(\gamma_m(h,u) = \gamma_{\text{joint}}(\sqrt{h^2 + (\kappa \cdot u)^2})\)

- \(\gamma_{\text{joint}}\) is any known variogram tha may generate a nugget effect

vgmST("metric", joint, stAni)- stAni: The anisotropy correction (\(\kappa\)) which is given in spatial unit per temporal unit (commonly m/s). For estimating this input, see

estiStAnibelow. Also see Terms >> Anisotropy

- stAni: The anisotropy correction (\(\kappa\)) which is given in spatial unit per temporal unit (commonly m/s). For estimating this input, see

- Assumes identical spatial and temporal covariance functions except for spatio-temporal anisotropy

- Sum-Metric

- A combination of spatial, temporal and a metric model including an anisotropy correction parameter, \(\kappa\)

- Covariance Function: \(C_{sm}(h,u) = C_s(h) + C_t(u) + C_{\text{joint}}(\sqrt{h^2 + (\kappa \cdot u)^2})\)

- Variogram: \(\gamma_{sm}(h,u) = \gamma_s(h) + \gamma_t(u) + \gamma_{\text{joint}}(\sqrt{h^2 + (\kappa \cdot u)^2})\)

- Where \(\gamma_s\), \(\gamma_t\), and \(\gamma_{\text{joint}}\) are spatial, temporal and joint variograms with separate nugget-effects

vgmST("sumMetric", space, time, joint, stAni)- Using the simple sum-metric model as starting values for the full sum-metric model improves the convergence speed.

- Simple Sum-Metric

- Removes the nugget effects from the three variograms in the Sum-Metric model

- Variogram: \(\gamma_{\text{sm}}(h,u) = \text{nug} \cdot \mathbb{1}_{h\gt0\; \vee \; u\gt0} + \gamma_s(h) + \gamma_t(u) + \gamma_{\text{joint}}(\sqrt{h^2 + (\kappa \cdot u)^2})\)

- Think the nugget indicator says only include the nuggect effect if h or u is greater than 0.

vgmST("simpleSumMetric", space, time, joint, nugget, stAni)

- Separable

fit.StVariogram

- Docs

- Fits the variogram model using the empirical variogram (

variogramST) and variogram model specification (vgmST) - Misc

extractPar(model)can be used to extract the estimated parameters from the variogram model

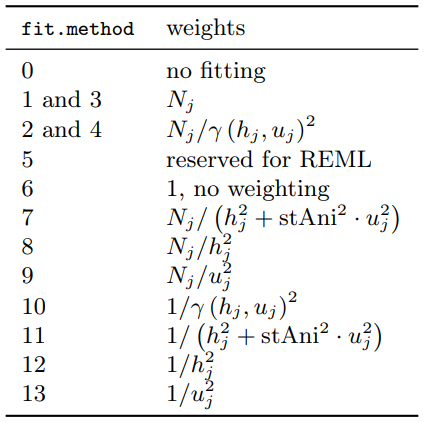

- Weighting Options

- Controls the weighing of the residuals between empirical and model surface

- tl;dr Even though 6 is the default, 7 seems like a sound statistical choice unless the data/problem makes another method make more sense.

- Adding Weights narrows down the spatial and temporal distances and introduces a cutoff.

- This ensures that the model is fitted to the differences over space and time actually used in the interpolation, and reduces the risk of overfitting the variogram model to large distances not used for prediction.

- To increase numerical stability, it is advisable to use weights that do not change with the current model fit. (?)

- Terms

- \(N_j\) is the number of location pairs for bin \(j\)

- \(h_j\) is the mean spatial distance for bin \(j\)

- \(u_j\) is the mean temporal distance for bin \(j\)

- Primarily two categories of methods:

- Equal-Bin - Have a 1 in the numerator which means only the denominator contributes

- Each lag bin contributes roughly equally to the objective function, regardless of how many point pairs went into estimating that bin.

- Consider with small datasets where \(N_j\) does not vary much across bins or when a balanced structure is called for.

- Precision-Weighted - Have \(N_j\) in the numerator

- Assumes bins with more location pairs provide more reliable empirical variogram estimates

- Parameter estimates tend to be more stable and less sensitive to small, noisy bins.

- Consider with moderate to large datasets with substantial variation in \(N_j\)

- Equal-Bin - Have a 1 in the numerator which means only the denominator contributes

- Methods

- fit.method = 6 (default) - No weights

- 1 and 3: Greater importance is placed on longer pairwise distance bins

- 2 and 10: Involve weights based on the fitted variogram that might lead to bad convergence properties of the parameter estimates.

- 7 and 11: Recommended to include the value of sfAni otherwise it’ll use the actual fitted spatio-temporal anisotropy which can lead the model to not converge.

estiStAnican be used to estimate the stAni value- The spatio-temporal analog to the commonly used spatial weighting

- Denominator referred to as the metric distance which is similar to the what’s used in the metric covariance model

- 7 puts higher confidence in lags filled with many pairs of spatio-temporal locations, but respects to some degree the need of an accurate model for short distances, as these short distances are the main source of information in the prediction step

- 3, 4, and 5: Kept for compatibility reasons with the purely spatial

fit.variogramfunction - 8 downweights more heaviliy the large pairwise distance bins (prioritizes small distance pairwise locations)

- 9 downweights more heavily the large pairwise time-distance bins (prioritizes small time-distance pairwise locations)

- stAni: The spatio-temporal anisotropy that is used in the weighting. Might be missing if the desired spatio-temporal variogram model already has the stAni parameter

- See Terms >> Anisotropy,

vgmST>> Metric, Sum Metric, and Simple Sum Metric - Default is NA and will be understood as identity (1 temporal unit = 1 spatial unit)

- Docs says this assumption is rarely the case so could be worth including to see if it improves performance

- Anisotropy Estimation Heuristics using

estiStAni- method = “linear” - Rescales a linear model

- method = “range” - Estimates equal ranges

- method = “vgm” - Rescales a pure spatial variogram

- method = “metric” - Estimates a complete spatio-temporal metric variogram model and returns its spatio-temporal anisotropy parameter.

- See Terms >> Anisotropy,

Diagnostics

- “The selection of a spatio-temporal covariance model should not only be made based on the (weighted) mean squared difference between the empirical and model variogram surfaces (

attributes(fit_vario)$value), but also on conceptional choices and visual judgement of the fits. (plot(emp_vario, c(fit_vario1, fit_vario2, fit_vario3), wireframe = TRUE, all = TRUE))” plot- Shows the sample and fitted variogram surfaces next to each other as colored level plots. (Docs)- wireframe = TRUE creates a wireframe plot

- diff = TRUE plots the difference between the sample and fitted variogram surfaces.

- Helps to better identify structural shortcomings of the selected model

- all = TRUE plots sample and model variogram(s) in single wireframes

- Convergence output from

optimmethod = “L-BFGS-B” is the default. It uses a limited-memory modification of the BFGS quasi-Newton method, and has been said not the be as robust as “BFGS” which is supposed to be the gold standard (thread). So if you have issues, “BFGS” may be worth a try.

Get these by accessing the optim.out attribute from

fit.StVariogramfit_var <- fit.StVariogram(...) attr_opt <- attributes(fit_var)$optim.out$convergence - The convergence code (guessing this just binary: converged or not converged (

attr_opt$convergence)$message - Probably gives more details about “not converged” or maybe the time, eps, etc.

$value - The mean of the (weighted) squared deviations (loss function) between sample and fitted variogram surface. (aka Weighted Mean Squared Error (wMSE))

- Check the estimated parameters against the parameter boundaries and starting values

- Be prepared to set upper and lower parameter boundaries if, for example, the sill parameters returned are negative.

Convergence Help

- Starting values can affect the results (hitting local optima) or even success of the optimization

- Using a starting value grid search might better asses the sensitivity of the estimates.

- Starting values can in most cases be read from the sample variogram.

- Parameters of the spatial and temporal variograms can be assessed from the spatio-temporal surface fixing the counterpart at 0.

- Example: Inspection of the ranges of the variograms in the temporal domain, suggests that any station more than at most 6 days apart does not meaningfully contribute

- The overall spatio-temporal sill including the nugget can be deducted from the plateau that a nicely behaving sample variogram reaches for ’large’ spatial and temporal distances.

- In some cases, you should rescale spatial and temporal distances to ranges similar to the ones of sills and nuggets using the parameter parscale.

- control = list(parscale=…) - Input a vector of the same length as the number of parameters to be optimized (See

optimdocs for details) - See vignette for an example. They used the simple sum-metric model to obtain starting values for the full sum-metric model, and that improved the convergence speed of the more complex model.

- There is a note in the discussion section about how this resulted in the more complex model being essentially the same as the simple model, but they tried other starting values and still ended up with the same result. So don’t freak if you get the same model.

- In most applications, a change of 1 in the sills will have a stronger influence on the variogram surface than a change of 1 in the ranges.

- control = list(parscale=…) - Input a vector of the same length as the number of parameters to be optimized (See

Interpolate

- A joint distance is formulated in the same manner as the metric covariance model, and then used to find a subset of data with k-NN for a prediction location. The interpolation performs iteratively for each spatiotemporal prediction location with that local subset of data.

- Other methods (staged search) and (octant search) are briefly described in the vignette but not implemented in {gstat}

krigeST(formula, data, modelList, newdata)- data - Original dataset (used to fit

variogramST) - modelList - Object returned from

fit.StVariogram - newdata - An ST object with prediction/simulation locations in space and time

- Should contain attribute columns with the independent variables (if present).

- computeVar = TRUE - Returns prediction variances

- fullCovariance = TRUE - Returns the full covariance matrix

- bufferNmax = 1 (default) - Used to increase the search radius for neighbors (e.g. 2 would be double the default radius.)

- A larger neighbourhood is evaluated within the covariance model and the strongest correlated nmax neighbours are selected

- If the prediction variances are large, then this parameter should help by gathering more data points.

- nmax - The maximum number of neighboring locations for a spatio-temporal local neighbourhood

- data - Original dataset (used to fit

stplot(preds)will plot the results- spat-temp vig

- Regular measurements over time (i.e. hourly, daily) motivate regular binning intervals of the same temporal resolution. Nevertheless, flexible binning boundaries can be passed for spatial and temporal dimensions. This allows for instance to use smaller bins at small distances and larger ones for large distances

- we could have fitted the spatial variogram for each day separately using observations from that day only. However, given the small number of observation stations, this produced unstable variograms for several days and we decided to use the single spatial variogram derived from all spatio-temporal locations treating time slices as uncorrelated copies of the spatial random field.

- A temporal lag of one or a few days leads already to a large variability compared to spatial distances of few hundred kilometres, implying that the temporal correlation is too weak to considerably improve the overall prediction.

- Further preprocessing steps might be necessary to improve the modelling of this PM10 data set such as for instance a temporal AR-model followed by spatio-temporal residual kriging or using further covariates in a preceding (linear) modelling step.

- Parameters of the spatial and temporal variograms can be assessed from the spatio-temporal surface fixing the counterpart at 0. (Done the spatial. How to do the temporal?)

- The prediction at an unobserved location with a cluster of observations at one side will be biased towards this cluster and neglect the locations towards the other directions. Similar as the quadrant search in the pure spatial case an octant wise search strategy for the local neighbourhood would solve this limitation. A simpler stepwise approach to define an n-dimensional neighbourhood might already be sufficient in which at first ns spatial neighbours and then from each spatial neighbour nt time instances are selected, such that

- Starting values can in most cases be read from the sample variogram

- need to see if a st empirical variogram can be plotted (or printed?) and what can actually be gleaned from it

- st vig

- spatio-temporal variogram settings

- width = 20, cutoff = 200 → ~10 spatial bins

- tlags = 0:15 → 16 temporal bins

- you now have ~160 bins.

- With more bins, you get more bins with few observations which causes