Inference

Misc

- Also see Mathematics, Statistics >> Descriptive >> Understanding CI, sd, and sem Bars

- {posterior} rvars class

- An object class that’s designed to:

- Interoperate with vectorized distributions in {distributional}

- Be able to be used inside data.frames and tibbles

- Be used with distribution visualizations in the {ggdist}

- Docs

- An object class that’s designed to:

- Remember CIs of parameter estimates including zero are not evidence of the null hypothesis (i.e. β = 0).

- Especially if CIs are broad and most of the posterior probability distribution is massed away from zero

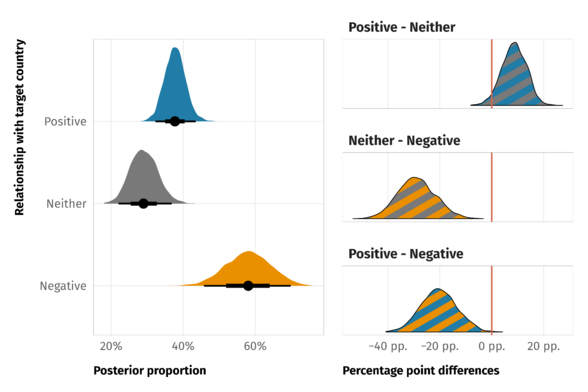

- Visualization for differences (Thread)

Significant Digits for Estimates

- Misc

- Notes from: Bayesian workflow book - Digits

- Before we can answer how many chains and iterations we need to run, we need to know how many significant digits we want to report

- MCMC in general doesn’t produce independent draws and the effect of dependency affects how many draws are needed to estimate different expectations

- Guidelines in general

- If the posterior would be close to a normal(μ,1), then

- For 2 significant digit accuracy,

- 2000 independent draws from the posterior would be sufficient for that 2nd digit to only sometimes vary.

- 4 chains with 1000 iterations after warmup is likely to give near two significant digit accuracy for the posterior mean. The accuracy for 5% and 95% quantiles would be between one and two significant digits.

- With 10,000 draws, the uncertainty is 1% of the posterior scale which would often be sufficient for two significant digit accuracy.

- For 1 significant digit accuracy, 100 independent draws would be often sufficient, but reliable convergence diagnostics may need more iterations than 100.

- For posterior quantiles, more draws may be needed (need more draws to get values towards the tails of the posterior)

- For 2 significant digit accuracy,

- Some quantities of interest may have posterior distribution with infinite variance, and then the ESS and MCSE are not defined for the expectation.

In such cases, use median instead of mean and median absolute deviation (MAD) instead of standard deviation.

Variance of parameter posteriors

as_draws_rvars(brms_fit) %>% summarise_draws(var = distributional::variance) #> variable var #> <chr> <dbl> #> 1 mu 11.6 #> 2 tau 12.8 #> 3 theta[1] 39.7 #> 4 theta[2] 21.5

- If the posterior would be close to a normal(μ,1), then

- Steps

- Check convergence diagnostics for all parameters

- e.g. RHat, ESS, autocorrelation plots (see Diagnostics, Bayes)

- Look at the posterior for quantities of interest and decide how many significant digits is reasonable taking into account the posterior uncertainty (using SD, MAD, or tail quantiles)

- You want to be able to distinguish you upper or lower CI from the point estimate

- e.g. Point estimate is 2.1 and your upper CI is 2.1, then you want at least another significant digit.

- You want to be able to distinguish you upper or lower CI from the point estimate

- Check that MCSE is small enough for the desired accuracy of reporting the posterior summaries for the quantities of interest.

- Calculate the range of variation due to MC sampling for your paramter (See MCSE example)

- MC sampling error is the average amount of variation that’s expected from changing seeds and re-running the analysis

- If the accuracy is not sufficient (i.e. range is too wide), report less digits or run more iterations.

- Calculate the range of variation due to MC sampling for your paramter (See MCSE example)

- Check convergence diagnostics for all parameters

- Monte Carlo Standard Error (MCSE) - The uncertainty about a parameter estimate due to MCMC sampling error

Packages

Example: brms, MCSE quantiles

library(posterior) # Coefficient and CI estimates for the "beta100" variable as_draws_rvars(brms_fit) %>% subset_draws("beta100") %>% summarize_draws(mean, ~quantile(.x, probs = c(0.05, 0.95))) #> variable mean 5% 95% #> beta100 1.966 0.673 3.242 as_draws_rvars(brms_fit) %>% subset_draws("beta100") %>% # select variable summarize_draws(mcse_mean, ~mcse_quantile(.x, probs = c(0.05, 0.95))) #> variable mcse_mean mcse_q5 mcse_q95 #> beta100 0.013 0.036 0.033- Specification

mcse_meanandmeanare available as preloaded functions thatsummarize_drawscan use out of the boxmcse_quantile(also in {posterior}) andquantileare not preloaded functions so they’re called as lambda functions- Not sure if this is true for

mcse_quantilesince it’s among the list of available diagnostics

- Not sure if this is true for

- These are MCSE values for

- The summary estimate (aka point estimate) which is the mean of the posterior in this case

- The CI values of that summary estimate

- Tail quantiles will have greater amounts of sampling error in the tails of the posterior than in the bulk (i.e. tail estimates are lest accurate)

- Fewer points means more uncertainty

- Calculate the range of variation due to Monte Carlo

- Multiplying the MCSE values by 2 gives the likely range of variation due to Monte Carlo which is

- Mean: ±0.02 (0.013 * 2 = 0.026)

- 5% and 95% Quantiles: ±0.07 (0.036 *2 = 0.072 and 0.033 * 2 = 0.066)

- Multiplying by 2, since I guess they’re assuming a normal distribution posterior, therefore estimate ± 1.96 * SE

- Multiplying the MCSE values by 2 gives the likely range of variation due to Monte Carlo which is

- Conclusion for beta100 coefficient

- If the mean estimate for beta100 is reported as 2 (rounded up from 1.966), then there is unlikely to be any variation in that estimate due to MCMC sampling. (i.e. okay to report the estimate as 2)

- This is because

- 1.966 + 0.02 = 1.986 which would still be rounded up to 2

- 1.966 - 0.02 = 1.946 which would still be rounded up to 2

- This is because

- If the mean estimate for beta100 is reported as 2 (rounded up from 1.966), then there is unlikely to be any variation in that estimate due to MCMC sampling. (i.e. okay to report the estimate as 2)

- Specification

- Draws and iterations

- With an MCSE in the 100ths (e.g. 0.07), 4 times more iterations would halve the MCSEs

- With an MCSE in the 1000ths (e.g. 0.007), 64 times more iterations would halve the MCSEs

- MCSEs depend on the quantity type. Continuous quantities (e.g. parameter estimates) have more information than discrete quantities (e.g. indicator values used to calculate probabilities).

- For example, above, the estimate for whether the temperature increase is larger than 4 degrees per century has high ESS, but the indicator variable contains less information (than continuous values) and thus much higher ESS would be needed for two significant digit accuracy.

Probabilistic Inference of Estimates

Misc

- Notes from: Bayesian workflow book - Digits

Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE)

- Packages: {bayestestR::rope} (Vignette)

- The scale dependence and threshold make significance arbitrary in my view. I can get past the threshold since it’s a practical-based decision that most people could probably agree upon what’s reasonable. The scale dependence is what really gets me — e.g. significance of an effect could depend on whether the variable was measured in centimeters or meters. I don’t know how you get past that.

- If I am ever convinced of this metric’s utility, then this article illustrates a nice workflow.

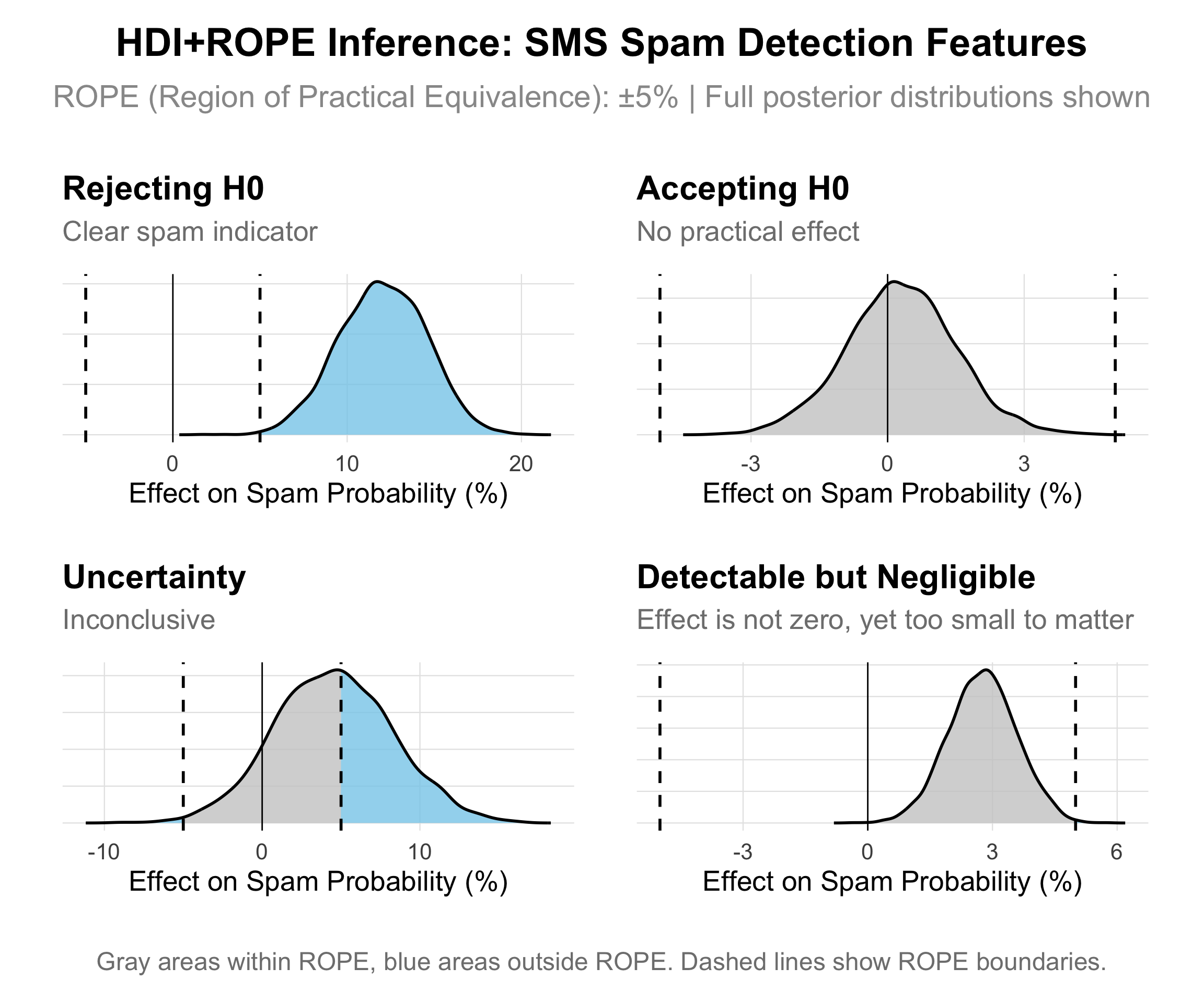

- Represents a shift from traditional significance testing to effect size reasoning. Rather than asking “Is there any effect, no matter how small?” (significance testing), we ask “Is the effect large enough to matter?” (effect size evaluation).

- It calculates a non-practically signficant region of the posterior. If this region composes too much of a percentage of the parameter’s posterior, then it is deemed insignificant

- Issues

- ROPE represents a fixed portion of the response’s scale, its proximity with a coefficient depends on the scale of the coefficient itself.

- Changing the scale of the predictor could determine whether it is deemed significant by this measure on not.

- Collinearity invalidates ROPE and hypothesis testing based on univariate marginals, as the probabilities are conditional on independence.

- When parameters show strong correlations, i.e. when covariates are not independent, the joint parameter distributions may shift towards or away from the ROPE

- Most problematic are parameters that only have partial overlap with the ROPE region

- Strong collinearity makes bayesian coefficients uninterpretable, which is always a concern, so I’m not as worried about missing this one.

- ROPE represents a fixed portion of the response’s scale, its proximity with a coefficient depends on the scale of the coefficient itself.

- Usage (source)

- Using 5% as a threshold (\(\pm 5\%\) ROPE)

- Reject the null hypothesis if less than 2.5% of the posterior distribution falls within the ROPE. This means we have strong evidence for a practically meaningful effect. The visualization below shows this as a distribution clearly extending beyond our the ROPE boundaries.

- Accept the null hypothesis if more than 97.5% of the posterior distribution falls within the ROPE. This means we have evidence for the practical absence of an effect—the parameter is essentially equivalent to zero in spam detection terms. This appears as a distribution tightly concentrated within the ROPE zone.

- Remain undecided if the percentage falls between these thresholds. The evidence is inconclusive at our current precision level, shown as distributions that substantially span the ROPE boundaries.

Probabilistic Ranges

Using MCSE to add uncertainty to the probabilistic inferences

** I think the predictor must be centered so that using predictor > some number in posterior can be in probabilistically interpreted like the way that these examples do **

Example 1: The probability that an estimate is positive

library(posterior) as_draws_rvars(brms_fit) %>% # binary 1/0, posterior samples > 0 mutate_variables(beta0p = beta100 > 0) %>% subset_draws("beta0p") %>% # select variable summarize_draws("mean", mcse = mcse_mean) #> variable mean mcse #> beta0p 0.993 0.001- 99.3% probability the estimate is above zero +/- 0.2% (= 2*MCSE)

- MCSE indicates that we have enough MCMC iterations for practically meaningful reporting that the probability that the variable (e.g. temperature) is increasing (i.e. slope is positive) is larger than 99%

Example 2: The probability that an estimate > 1, 2, 3, and 4

library(posterior) as_draws_rvars(brms_fit) %>% subset_draws("beta100") %>% # binary 1/0 variable mutate_variables(beta1p = beta100 > 1, beta2p = beta100 > 2, beta3p = beta100 > 3, beta4p = beta100 > 4) %>% subset_draws("beta[1-4]p", regex=TRUE) %>% summarize_draws("mean", mcse = mcse_mean, ESS = ess_mean) #> variable mean mcse ESS #> beta1p 0.896 0.006 3020 #> beta2p 0.487 0.008 4311 #> beta3p 0.088 0.005 3188 #> beta4p 0.006 0.001 3265- Taking into account MCSEs given the current posterior sample, we can summarize these as:

\[ \begin{align} P(\text{beta100} > 1) &= 88\% \;\text{to}\; 91\% \\ P(\text{beta100} > 2) &= 46\% \;\text{to}\; 51\% \\ P(\text{beta100} > 3) &= 7\% \;\text{to}\; 10\% \\ P(\text{beta100} > 1) &= 0.2\% \;\text{to}\; 1\% \\ \end{align} \]- Remember to take 2*MCSE to get the upper and lower limits

- To get these probabilities estimated with 2 digit accuracy would again require more iterations (16-300 times more iterations depending on the quantity), but the added iterations would not change the conclusion radically.

- Taking into account MCSEs given the current posterior sample, we can summarize these as:

Probability of Direction (PD)

\[ p_d = max({Pr(\hat{\theta} < \theta_{null}), Pr(\hat{\theta} > \theta_{null})}) \]

- AKA Maximum Probability of Effect (MPE)

- See {bayestestR::p_direction} for further details

- Properties

- PD has a direct correspondence with the frequentist one-sided p-value through the formula (for two-sided p-value): \(\text{p-value} = 2 \cdot (1 - p_d)\)

- PD is solely based on the posterior distributions and does not require any additional information from the data or the model (e.g., such as priors, as in the case of Bayes factors).

- It is robust to the scale of both the response variable and the predictors.

- Ranges

- These values are presented as a percentage

- Continuous Parameter Space: [0.5, 1]

- Similar to p-values, values close to 0.5 can not be used to support the Null

- Discrete Parameter Space: [0, 1]

- Discrete space examples: discrete-only parameters, bayesian model averaging

- Or a parameter space that is a mixture between discrete and continuous spaces (e.g. spike-and-slab prior)

- Values close to 0 can be used to support the null hypothesis

Bayes Factors (BF)

- See Diagnostics, Bayes >> Predictive Accuracy >> Bayes Factors for more details

- Packages

- {bayestestR::bf_parameters} (Vignette) - Computes Bayes factors against the null (either a point or an interval), based on prior and posterior samples of a single parameter.

- {effectsize::interpret_bf} - Uses Jeffreys (1961) or Raftery (1995) guidelines to determine the strength of evidence

- For parameter testing, it answers, “Given the observed data, has the null hypothesis of an absence of an effect become more or less credible?”

- The Bayes factor indicates the degree by which the mass of the posterior distribution has shifted further away from or closer to the null value(s) (relative to the prior distribution), thus indicating if the null value has become less or more likely given the observed data.