Optimization

Misc

- Packages

- {atime} - Computing and visualizing comparative asymptotic timings of different algorithms and code versions.

- Compare time/memory/other quantities of different R codes that depend on N:

atime() - Estimate the asymptotic complexity (big-O notation) of any R code that depends on some data size N:

references_best() - Compare time/memory of different git versions of R package code:

atime_versions() - Continuous performance testing of R packages:

atime_pkg()

- Compare time/memory/other quantities of different R codes that depend on N:

- {line_profiler} - A module for doing line-by-line profiling of functions. kernprof is a convenient script for running either line_profiler or the Python standard library’s cProfile or profile modules, depending on what is available.

- {pipetime} - Measures and logs code execution time within pipes

- {syrup} - Measure Memory and CPU Usage for Parallel R Code

- {memuse} - Memory Estimation Utilities

- Finds memory usage for would-be objects (e.g. matrices), current usage, remaining RAM, and more

- {atime} - Computing and visualizing comparative asymptotic timings of different algorithms and code versions.

- Tools

- Some orchestration platforms provide monitoring for execution time, memory usage, and I/O operations for you and are flexible enough for you to add whatever asset or runtime metadata you need (e.g. Dagster)

- Memory issues often masquerade as performance issues.

- A function that “takes forever” is usually thrashing swap because it’s trying to load 20GB into 8GB of RAM. The fix isn’t faster Python, it’s chunked processing or better data architecture.

- Common less-valuable optimizations (source)

String concatenation in small loops

result = "" for item in small_list: # <1000 items result += itemList comprehensions vs. map

# These are functionally identical in performance: [x * 2 for x in range(1000)] list(map(lambda x: x * 2, range(1000)))Micro-optimizations in code that runs once

- If your pipeline does something once per run (loading config, initializing connections), optimizing that code is pointless

Function call overhead

- Yes, function calls have overhead. No, it doesn’t matter for data pipelines. A function call costs ~100 nanoseconds. Your database query costs 500 milliseconds. Do the math.

- Guidelines (source)

- Don’t optimize if you’re:

- Optimizing code that runs infrequently

- Optimizing before measuring

- Optimizing Python/R when the database is the bottleneck

- Adding complexity to save <10% runtime

- Optimizing because it’s “more elegant”

- Using a “faster” library you don’t understand

- Parallel processing without checking if you’re I/O-bound

- Start optimizing if:

- Pipeline misses SLA regularly

- Profiling shows clear bottleneck (>50% of runtime)

- Bottleneck is CPU/memory-bound in your code

- Optimization has clear ROI (time saved × frequency)

- You’ve already fixed the database queries

- Users are actually waiting for results

- Don’t optimize if you’re:

- Common valuable optiimizations (source)

- Database queries

- e.g. Adding an index, fixing a join, or using proper partitioning

- Unnecessary data loading

- Only load the data you need.

- e.g. Parquets partitioned by date allow you to only read that date’s parquet file. Lots of data reading functions allow you to chunk, filter rows, or select columns when reading in data.

- Inefficient iteration patterns

- e.g. use vectorized functions wherever possible

- Serialization/deserialization in tight loops

Example: Batching and json serializers

# Bad: JSON parsing in a loop for streaming data for record in stream: data = json.loads(record) # Parsing overhead process(data) # Good: Batch and use faster serialization batch = [] for record in stream: batch.append(record) if len(batch) >= 1000: data = orjson.loads(batch) # Faster JSON library, batched process_batch(data)

- Retry logic without exponential backoff

- See APIs >> {requests} >> Rate Limiting >> {tenacity} example

- Reduces API failures from 15% to <1% by avoiding rate limit cascades. Makes pipelines more resilient to transient failures.

- Memory churn from repeated allocation

Example

# Bad: Creating new objects in a hot loop for i in range(1_000_000): result = {} # New dict allocation every iteration result['key'] = expensive_calc(i) results.append(result) # Good: Reuse or pre-allocate results = [{'key': expensive_calc(i)} for i in range(1_000_000)] # Or use numpy/pandas which handle memory efficiently

- Database queries

- A while loop is faster than a recursive function

- ungroup before performing calculations in mutate or summarize when that calculation doesn’t need to be performed within-group (i.e. per factor level)

- String functions

- “fixed” searches,

fixed = TRUEare fastest overall- Searches involving fixed strings (e.g. “banana”) that don’t require regular expressions

- PCRE2,

perl = TRUE, is fastest for regular expressions

- “fixed” searches,

- Adding Rows to a Matrix (link, link)

rbindis very slow andcbind+t()isn’t much betterfrbind <- function(n) { res <- vector() for (i in 1:n) { res <- rbind(res, runif(n)) } res } fcbind <- function(n) { res <- vector() for (i in 1:n) { res <- cbind(res, runif(n)) } t(res) }Add rows to a list then combine into a matrix

# grow list which is converted to a matrix at the end. flist <- function(n) { res <- list() for (i in 1:n) { res[[length(res) + 1]] <- runif(n) } do.call(rbind, res) } flist2 <- function(n) { res <- list() for (i in 1:n) { res[[length(res) + 1]] <- runif(n) } len <- length(res) res <- res |> purrr::list_c() dim(res) <- c(len, len) res }list_cuses C under the hood and might be faster on larger matrices.

pmax: Usen[n<1] <- 1ranther thann<-pmax(n,1)(source)

Benchmarking

- Misc

- Mastering Software Development in R, Ch. 2.71

- {bench}

Misc

- Automatically checks that each approach gives the same output, so that you don’t mistakenly compare apples and oranges

bench::markcreates a very large output object. The one in Vectorization Workflows >> Example 1 was 400MB. RStudioViewlocked up when I tried to look at it. There are large dataframes nested within the memory and result columns. Setting the option memory = FALSE only decreases the size of the object very little. Compilation of this object will take a minute or two after the benchmark has technically finished.

Example: Basic

res <- bench::mark( approach_1 = Reduce(sum, numbers), approach_2 = sum(unlist(numbers)) ) res %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 2 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 approach_1 2.25µs #> 2 approach_2 491.97ns

- {microbenchmark}

-

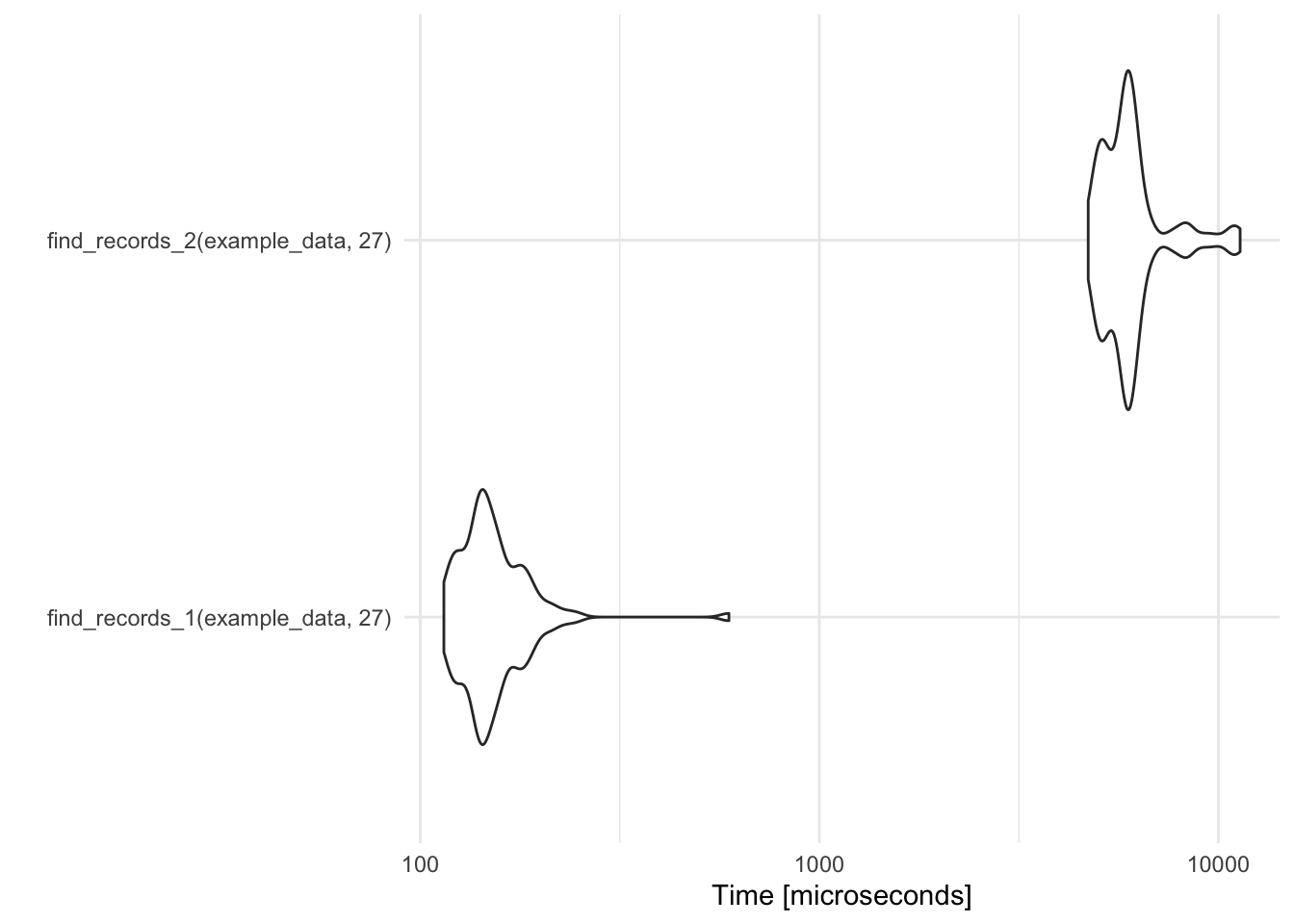

record_temp_perf <- microbenchmark(find_records_1(example_data, 27), find_records_2(example_data, 27)) record_temp_perf ## Unit: microseconds ## expr min lq mean median uq ## find_records_1(example_data, 27) 114.574 136.680 156.1812 146.132 163.676 ## find_records_2(example_data, 27) 4717.407 5271.877 6113.5087 5867.701 6167.709 ## max neval ## 593.461 100 ## 11334.064 100 library(ggplot2) autoplot(record_temp_perf)- Default: 100 iterations

- Times are given in a reasonable unit, based on the observed profiling times (units are given in microseconds in this case).

- Output

- min - min time

- lq - lower quartile

- mean, median

- uq - upper quartile

- max - max time

-

Profiling

- Misc

- Resources

- Packages

- {profvis} - Interactive Visualizations for Profiling R Code

- {profmem}: Simple Memory Profiling for R

- {syrup}: Provide measures of memory and CPU usage for parallel R code

- {memuse} - An R package for memory estimation.

- Tools for estimating the size of a matrix (that doesn’t exist), showing the size of an existing object in a nicer way than

object.size(). It also has tools for showing how much memory the current R process is consuming, how much ram is available on the system, and more.

- Tools for estimating the size of a matrix (that doesn’t exist), showing the size of an existing object in a nicer way than

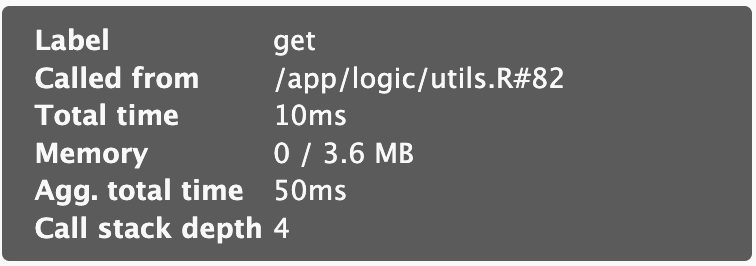

- {profvis}

Notes from Unveiling Bottlenecks (Part 2): A Deep Dive into Profiling Tools

Features

- Vertical Bars: Each vertical bar in the flame graph represents a function call stack in your code. The height of the bar indicates the depth of the call stack, with the top-most bar representing the outermost function call.

- Colors: Different colors are used to distinguish between different functions or code blocks. Colors often depict different code categories (e.g., user code, Shiny functions, R base functions).

- Width of Bars: The width of each bar corresponds to the amount of time spent executing the function. Wider bars indicate that more time was spent in that particular function.

- Clicking on Bars: Clicking on a bar representing a function call often reveals additional information such as the function name, self time (time spent within the function), and total time (including time spent in functions it calls).

- Clicking on Cells: Single click on cell will move you to the specific function, double click on cell will redirect you to code editor in a separate window, additionally it will expand the bar to provide you a more clear view.

- Data Tab: A hierarchical table showing the profile in a top-down manner. Allows you to check the Memory and Time columns for resource allocation insights.

Analyzing the Flame Graph

Identifying Bottlenecks: Look for sections with the widest bars. These represent functions that consume the most execution time and are potential bottlenecks.

Understanding Call Stack: Trace the path downwards from the top to identify the sequence of function calls leading to the bottleneck.

Zooming In: Use interactive features to zoom in on specific sections for a closer look at nested function calls.

Comparing Runs: You can compare flame graphs from different app versions to identify performance improvements or regressions.

Interpreting the Information

Time Spent in Functions: The width of a bar at a specific level reveals the time spent executing that particular function.

Self Time vs. Total Time: Some profvis implementations differentiate between “self time” (time spent within the function itself) and “total time” (including time spent in functions it calls). This helps identify functions that contribute significantly to bottlenecks through nested calls.

Code Optimization: By focusing on functions with the widest bars, you can prioritize optimization efforts by re-factoring code, leveraging vectorization, or exploring alternative algorithms.

-

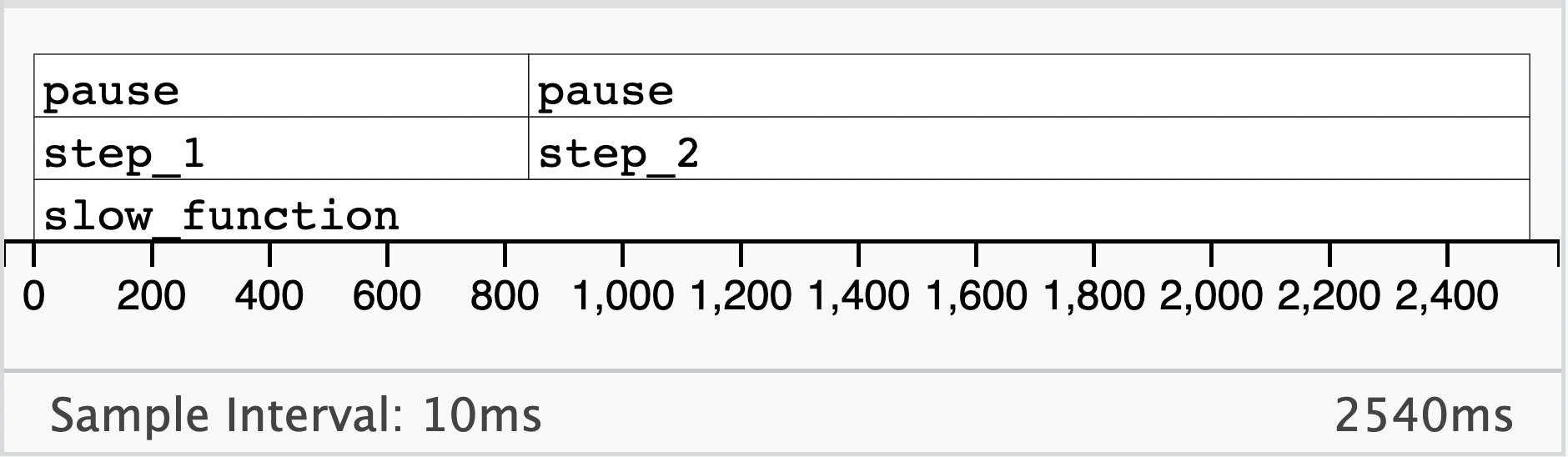

step_1 <- function() { pause(1) } step_2 <- function() { pause(2) } slow_function <- function() { step_1() step_2() TRUE } result <- profvis(slow_function()) result- Bottom Row: outermost function

- 2nd Row from the bottom are the functions in the next enviromental layer (e.g. “step_1” and “step_2”)

- “step_2” takes about 2/3 of the total function execution time or twice the execution time of “step_1”

- 3rd Row from the bottom (top row) are the functions in each of those other functions

- “pause” in “step_2” takes about 2/3 of the total function execution time or twice the execution time of “pause” in “step_1”

Python

Benchmarking

{time} (built-in module)

import time start = time.perf_counter() time.sleep(1) # do work elapsed = time.perf_counter() - start print(f'Time {elapsed:0.4}') #> Time 1.001

{cProfile}

For CPU operations

Example: Basic Workflow

import cProfile import pstats profiler = cProfile.Profile() profiler.enable() # Your code here expensive_function() profiler.disable() stats = pstats.Stats(profiler) stats.sort_stats('cumulative') stats.print_stats(10) # Top 10 slowest functions

Memory Usage

- {{memory-profiler}}

Basic usage for a function

from memory_profiler import memory_usage mem, retval = memory_usage((fn, args, kwargs), retval=True, interval=1e-7)interval: For very quick operations the function

fnmight be executed more than once. By settingintervalto a value lower than 1e-6, we force it to execute only once.retval: Tells the function to return the result of fn.

Example: Basic usage with profile decorator

from memory_profiler import profile @profile def load_giant_dataframe(): """This will show line-by-line memory usage.""" df = pd.read_csv("10gb_file.csv") # This will show line-by-line memory return df.groupby("key").sum()Non-interactive usage

$ python -m memory_profiler example.py #> Line # Mem usage Increment Line Contents #> ============================================== #> 3 @profile #> 4 5.97 MB 0.00 MB def my_func(): #> 5 13.61 MB 7.64 MB a = [1] * (10 ** 6) #> 6 166.20 MB 152.59 MB b = [2] * (2 * 10 ** 7) #> 7 13.61 MB -152.59 MB del b #> 8 13.61 MB 0.00 MB return a

- {{memory-profiler}}

Profile decorator

import time from functools import wraps from memory_profiler import memory_usage def profile(fn): @wraps(fn) def inner(*args, **kwargs): fn_kwargs_str = ', '.join(f'{k}={v}' for k, v in kwargs.items()) print(f'\n{fn.__name__}({fn_kwargs_str})') # Measure time t = time.perf_counter() retval = fn(*args, **kwargs) elapsed = time.perf_counter() - t print(f'Time {elapsed:0.4}') # Measure memory mem, retval = memory_usage((fn, args, kwargs), retval=True, timeout=200, interval=1e-7) # Get Peak Memory Usage print(f'Memory {max(mem) - min(mem)}') return retval return inner @profile def work(n): for i in range(n): 2 ** n work(10) #> work() #> Time 0.06269 #> Memory 0.0 work(n=10000) #> work(n=10000) #> Time 0.3865 #> Memory 0.0234375

Replacements for Tidyverse Functions

Misc

- Notes from: Writing performant code with tidy tools

- Also provides links to more {vctrs} recipes from their tidymodels github pull requests

- For code that relies on

group_by()and sees heavy traffic, seevctrs::list_unchop(),vctrs::vec_chop(), andvctrs::vec_rep_each(). - Drop-in, low-dependency replacements

vec_if_else,vec_case_when,vec_replace_when,vec_recode_values,vec_replace_values

- Notes from: Writing performant code with tidy tools

select

bench::mark( dplyr = select(mtcars_tbl, hp), `[.tbl_df` = mtcars_tbl["hp"] ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 2 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 dplyr 527.01µs #> 2 [.tbl_df 8.08µs- Winner: base R subsetting

filter

Wres <- bench::mark( dplyr = filter(mtcars_tbl, hp > 100), vctrs = vec_slice(mtcars_tbl, mtcars_tbl$hp > 100), `[.tbl_df` = mtcars_tbl[mtcars_tbl$hp > 100, ] ) %>% select(expression, median) res #> # A tibble: 3 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 dplyr 289.93µs #> 2 vctrs 4.63µs #> 3 [.tbl_df 23.74µs- Winner:

vctrs::vec_slice

- Winner:

mutate

bench::mark( dplyr = mutate(mtcars_tbl, year = 1974L), `$<-.tbl_df` = {mtcars_tbl$year <- 1974L; mtcars_tbl} ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 2 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 dplyr 302.5µs #> 2 $<-.tbl_df 12.8µs- Winner: base R assignment

mutate and relocate

bench::mark( mutate = mutate(mtcars_tbl, year = 1974L, .after = make_model), relocate = relocate(mtcars_tbl, year, .after = make_model), `[.tbl_df` = mtcars_tbl[ c(left_cols, colnames(mtcars_tbl[!colnames(mtcars_tbl) %in% left_cols]) ) ], check = FALSE ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 3 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 mutate 1.2ms #> 2 relocate 804.3µs #> 3 [.tbl_df 19.1µs- Winner: base R

pull

bench::mark( dplyr = pull(mtcars_tbl, hp), `$.tbl_df` = mtcars_tbl$hp, `[[.tbl_df` = mtcars_tbl[["hp"]] ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 3 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 dplyr 101.19µs #> 2 $.tbl_df 615.02ns #> 3 [[.tbl_df 2.25µs- Winner: base R bracket subsetting

bind_*

bench::mark( dplyr = bind_rows(mtcars_tbl, mtcars_tbl), vctrs = vec_rbind(mtcars_tbl, mtcars_tbl) ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 2 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 dplyr 44µs #> 2 vctrs 14.3µs bench::mark( dplyr = bind_cols(mtcars_tbl, tbl), vctrs = vec_cbind(mtcars_tbl, tbl) ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 2 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 dplyr 60.7µs #> 2 vctrs 26.2µs- Winners:

vctrs::vec_cbindandvctrs::vec_rbind

- Winners:

Create Tibble

bench::mark( tibble = tibble(a = 1:2, b = 3:4), new_tibble_df_list = new_tibble(df_list(a = 1:2, b = 3:4), nrow = 2), new_tibble_list = new_tibble(list(a = 1:2, b = 3:4), nrow = 2) ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 3 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 tibble 165.97µs #> 2 new_tibble_df_list 16.69µs #> 3 new_tibble_list 4.96µs- Winner:

new_tibble_list

- Winner:

Joins

Questions:

- If this join happens multiple times, is it possible to express it as one join and then subset it when needed?

- i.e. if a join happens inside of a loop but the elements of the join are not indices of the loop, it’s likely possible to pull that join outside of the loop and then

vctrs::vec_slice()its results inside of the loop. Am I using the complete outputted join result or just a portion? If I end up only making use of column names, or values in one column (as with joins approximating lookup tables), or pairings between two columns, I may be able to instead use$.tbl_dfor[.tbl_df(see above, Pull).

- i.e. if a join happens inside of a loop but the elements of the join are not indices of the loop, it’s likely possible to pull that join outside of the loop and then

- If this join happens multiple times, is it possible to express it as one join and then subset it when needed?

For problems even a little bit more complex, e.g. if there were possibly multiple matching or if I wanted to keep all rows, then expressing this join with more bare-bones operations quickly becomes less readable and more error-prone. In those cases, too, joins in dplyr have a relatively small amount of overhead when compared to the vctrs backends underlying them. So, optimize carefully.

Example:

inner_joinvsvctrs::vec_slice(Note: *only 0 or 1 match possible*)supplement_my_cars <- function() { # locate matches, assuming only 0 or 1 matches possible loc <- vec_match(my_cars$make_model, mtcars_tbl$make_model) # keep only the matches loc_mine <- which(!is.na(loc)) loc_mtcars <- vec_slice(loc, !is.na(loc)) # drop duplicated join column my_cars_join <- my_cars[setdiff(names(my_cars), "make_model")] vec_cbind( vec_slice(mtcars_tbl, loc_mtcars), vec_slice(my_cars_join, loc_mine) ) } supplement_my_cars() #> # A tibble: 1 × 13 #> make_model mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb #> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> #> 1 Honda Civic 30.4 4 75.7 52 4.93 1.62 18.5 1 1 4 2 #> # ℹ 1 more variable: color <chr> bench::mark( inner_join = inner_join(mtcars_tbl, my_cars, "make_model"), manual = supplement_my_cars() ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 2 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 inner_join 438µs #> 2 manual 50.7µs

nest

bench::mark( nest = nest(mtcars_tbl, .by = c(cyl, am)), vctrs = { res <- vec_split( x = mtcars_tbl[setdiff(colnames(mtcars_tbl), nest_cols)], by = mtcars_tbl[nest_cols] ) vec_cbind(res$key, new_tibble(list(data = res$val))) } ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 2 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 nest 1.81ms #> 2 vctrs 67.61µs # Results of nesting #> # A tibble: 6 × 3 #> cyl am data #> <dbl> <dbl> <list> #> 1 6 1 <tibble [3 × 10]> #> 2 4 1 <tibble [8 × 10]> #> 3 6 0 <tibble [4 × 10]> #> 4 8 0 <tibble [12 × 10]> #> 5 4 0 <tibble [3 × 10]> #> 6 8 1 <tibble [2 × 10]>glue and paste0

vec_paste0 <- function (...) { args <- vec_recycle_common(...) exec(paste0, !!!args) } name <- "Simon" bench::mark( glue = glue::glue("My name is [{name}]{style='color: #990000'}."), vec_paste0 = vec_paste0("My name is ", name, "."), paste0 = paste0("My name is ", name, "."), check = FALSE ) %>% select(expression, median) #> # A tibble: 3 × 2 #> expression median #> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> #> 1 glue 38.99µs #> 2 vec_paste0 3.98µs #> 3 paste0 861.01nspaste0()has some tricky recycling behavior.vec_paste0is a middle ground in terms of both performance and safety.- Use

glue()for errors, when the function will stop executing anyway. - For simple pastes that are intended to be called repeatedly, use

vec_paste0().

Vectorization Workflows

- Misc

- Packages

- {oomph} - Faster subsetting of vectors and lists by name

- Packages

- Example 1: Lookup Vectors vs Left Joins

1removal_effects_table <-

dplyr::tibble (

channel_name = c("fb","tiktok","gda","yt","gs","rtl","blog"),

removal_effects_conversion = c(.2,.1,.3,.1,.6,.05,.09)

)

head(path10k, n = 10)

#> # A tibble: 10 × 4

#> path dates leads value

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 tiktok>blog>gs>fb>rtl 2023-04-17>2023-02-25>2023-01-24>2023-03-12>2023-03-09 1 6794.

#> 2 yt>blog>gs>fb>gda 2023-01-18>2023-01-27>2023-02-19>2023-01-01>2023-04-30 1 5981.

#> 3 fb>gs>yt 2023-04-21>2023-02-20>2023-03-23 1 5801.

#> 4 gda>yt>tiktok>blog 2023-04-24>2023-03-01>2023-05-03>2023-04-29 1 4583.

#> 5 rtl 2023-02-20 1 6735.

#> 6 gda>yt>rtl>tiktok 2023-02-04>2023-02-26>2023-01-09>2023-03-22 1 7238.

#> 7 tiktok>blog 2023-03-06>2023-04-20 1 9041.

#> 8 gda>tiktok>rtl>yt>gs 2023-05-02>2023-03-25>2023-04-26>2023-03-19>2023-03-28 1 8560.

#> 9 tiktok>rtl>blog>gda>gs 2023-04-16>2023-04-24>2023-03-31>2023-02-10>2023-01-05 1 4653.

#> 10 gda>fb 2023-01-23>2023-05-05 1 7125.

# Desired Output

#> channel_name re conversion value dates

#> 1: tiktok 0.10 0.09615385 653.2879 2023-04-17

#> 2: blog 0.09 0.08653846 587.9591 2023-02-25

#> 3: gs 0.60 0.57692308 3919.7273 2023-01-24

#> 4: fb 0.20 0.19230769 1306.5758 2023-03-12

#> 5: rtl 0.05 0.04807692 326.6439 2023-03-09- 1

- retbl input in the function that gets joined with path10k in the dplyr version and is used to create the look-up vector.

join_attr <- function(path_str, date_str, outcome, value, retbl){

# Will remain the same in base R

1 touches <- stringr::str_split_1(path_str, ">")

dates <- stringr::str_split_1(date_str, ">")

2 dates <- dates[touches != '']

touches <- touches[touches != '']

tidyr::tibble(channel_name = touches,

3 date = dates) |>

dplyr::left_join(

retbl |>

dplyr::select(channel_name,

removal_effects_conversion),

by = 'channel_name'

) |>

dplyr::rename(

re = removal_effects_conversion

) |>

dplyr::mutate(

# re/sum(re) normalizes value

conversion = outcome * re / sum(re, na.rm = T),

value = value * re / sum(re, na.rm = T)

)

}- 1

- Break the path_str and date_str character vectors into vectors of touch points and dates

- 2

- Remove empty values in dates and touches

- 3

- Create an output dataframe that shows the fraction of a lead due to touches/channel_name

1lu <- setNames(

2 removal_effects_table[["removal_effects_conversion"]],

3 removal_effects_table[["channel_name"]]

)

lu

#> fb tiktok gda yt gs rtl blog

#> 0.20 0.10 0.30 0.10 0.60 0.05 0.09

look_attr <- function(path_str, date_str, outcome, value, lu) {

touches <- stringr::str_split_1(path_str,">")

dates <- stringr::str_split_1(date_str,">")

dates <- dates[touches != '']

touches <- touches[touches != '']

4 re <- lu[touches]

re_tot <- sum(re, na.rm = TRUE)

conversion <- outcome * re / re_tot

value <- value * re / re_tot

tibble::tibble(

channel_name = touches,

re,

conversion,

value,

date = dates

)

}- 1

-

A look-up vector (i.e. named numeric vector), which is similar to how retbl is used in the

left_join, is preferable to the join since only a df with a name and value column was being joined. - 2

- These are the values for the look-up vector

- 3

- These are the names for the look-up vector

- 4

- Pulls the re value from the look-up vector based on the touch name

- This solution still requires loopling through each row. See Benchmark Section.

lu <- setNames(

removal_effects_table[["removal_effects_conversion"]],

removal_effects_table[["channel_name"]]

) # See base R section for details

vec_look_attr <- function(.data, .lu) {

1 touches <- strsplit(.data$path,

">",

fixed = TRUE)

2 lt <- lengths(touches)

3 groups <- rep.int(seq_along(touches), lt)

4 outcome <- rep.int(.data$leads, lt)

value <- rep.int(.data$value, lt)

5 touches <- unlist(touches)

dates <- unlist(strsplit(.data$dates,

">",

fixed = TRUE))

not_empty <- touches != ''

dates <- dates[not_empty]

touches <- touches[not_empty]

re <- .lu[touches]

DT <- data.table(

channel_name = touches,

outcome = outcome,

date = dates,

re,

value,

groups

)

DT[,

re_tot := sum(re, na.rm = TRUE),

by = groups]

DT[, `:=`(conversion = outcome * re / re_tot,

value = value * re / re_tot)]

DT[,.(channel_name, re, conversion, value, date)]

}- 1

- Split all the strings in all the rows all at once. This creates a large list of character vectors — one for each row of the dataset.

- 2

- Calculates the length of each character vector of the list.

- 3

- Creates an index variable that specifies which character vector (i.e. row of dataset) that each element of the vectors belongs. For example, if the 2nd character vector had 5 elements, then there will be a sequence of five 2s in this index variable. This will be grouping variable that will be needed for group calculations. It seems to represent a session or user in this context.

- 4

-

There is no

seq_alonghere, so each value of the vector (e.g. lead, value) gets repeated the number of times that is the length of the character vector associated with it in the touches list. - 5

- Unlisting touches combines all the character vectors in the list into one long character vector. The same processing is also done for dates since it also has multiple values per row. Now all the variables are ready to be put into the expanded df.

- Steps 3 and 4 are in a sense acting like a manual version of

expand.grid. We want each string in touches (formally path) to eventually get its own row in the resultant df. These steps repeat the values of the other vectors in the original dataset in order to fill out the rows of this larger df. - With the expanded df, there is no need to loop through rows, and we can perform column operations like normal which gives us peak performance in R.

- Along with this vectorized expansion, the look-up vector is also employed.

bm <- bench::mark(

look = data.table::rbindlist(

purrr::pmap(

list(path_str = path_data$path,

date_str = path_data$dates,

outcome = path_data$leads,

value = path_data$value),

look_attr,

lu,

.progress = 'base_r_level'

)

),

vecexp_look = vec_look_attr(path_data, lu)

)

bm |>

dplyr::select(1:5) |>

dplyr::mutate(

times_faster = as.double(dplyr::lag(median, 1) / median)

)

#> expression min median `itr/sec` mem_alloc times_faster

#> <bch:expr> <bch:tm> <bch:tm> <dbl> <bch:byt> <dbl>

#> 1 look 18.5s 18.5s 0.0542 43.52MB NA

#> 2 vecexp_look 14.5ms 17ms 52.6 9.03MB 1082.- I didn’t include the Left-Join version because it wasn’t going to win. If you want to see the comparison, see the video or github links. (It was about 7 times slower than the Look-Up version)

- I also didn’t include the Rust version, because I currently don’t know enough about Rust to fool with it right now.

- The Expansion+Look-Up version was a 1000 times faster than the base R version.

- The Look-Up version only partially vectorizes using the look-up vector, but also has to complete slow row operations.

- The Expansion+Look-Up version vectorizes the expansion of the string values in the path and dates variables, and also uses the look-up vector.

- Not only did the Expansion+Look-Up version win, it had a substantially smaller memory allocation (5 times smaller).